Will AI Shaft the Lawyer?

By Jaskaran Singh Kohli

Published on August 2, 2017

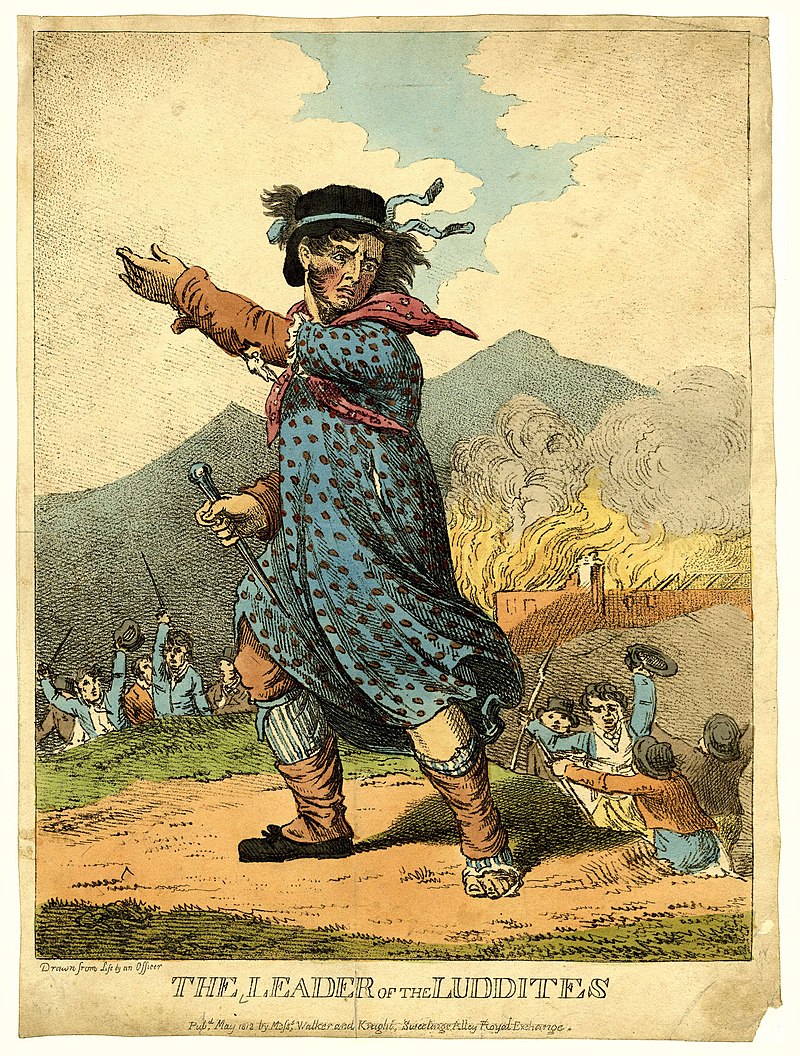

The Luddite rebellions at the beginning of the 19th century remained largely un-commemorated 200 years later. However, the unsuccessful workers rebellion, in which textile workers destroyed weaving machinery to protest unfair labour practices, has never been more relevant.

Trump’s popularity in the rust-belt was somewhat driven by the belief that he would stem the rate of change in the labour market, where blue collar jobs have fallen at the hands of automation and globalisation, all enabled by advances in technology.

Further, chants of ‘de-growth’ in Italy and minimum income initiative gaining steam across the developed world echo the calls of the Luddites for a lateral moral code governing the use of technology.

Where blue collar workers have been the traditional victims of automation, development of bots and breakthroughs in AI technologies may see lawyers as the next victim to technology.

The legal sector, being considered a conservative profession characterised by fusty old men in dusty old wigs, will probably be the last to attract any sympathy. Digital technologies have already changed the constitution of the legal sector: developing the way people and information are managed and therefore how law is practiced overall. To date, this has mostly benefitted the lawyer by withdrawing the need for typists and clerks, bumping up productivity and profit in turn.

But breakthroughs in software such IBM’s ROSS and RAVN may bring startling changes to the standard of legal practice and may even threaten to wipe out the role of a lawyer altogether.

The ready availability of such software and technology may have a revising effect on the role of lawyers and questions may arise as to whether there needs to be competence in their use. Just as lawyers today are expected to type up rather than handwrite formal work, the ability to use AI may eventually become the required standard of the legal profession.

The function of RAVN’s Artificial Intelligence platform, RAVN ACE, is rather quaintly summarised as ‘apply[ing] rules in an expert system in order to offer a solution.’

In reality, it powers a number of applications to automatically read, interpret and summarise key information from documents and unstructured data and is said to able to process thousands of contracts in a matter of seconds.

This is, in effect, a computer that performs the key functions of a lawyer, processing unstructured data and applying its expertise.

By inputting the details of a case as RAVN does, they can determine the chance of success to get better synopses of a case and determine the chance of success.

However, questions of conduct amongst lawyers may arise resulting from these new developments.

It may, in these new times, be harmful for a lawyer to be too honest for his own good and so lawyers may be tempted ignore or become wilfully blind to AI where AI indicates little chance of success in litigation proceedings. However, leading a client down a path that is not in his best interest and encouraging him to cover legal fees for a case that is clearly a dud certainly raises ethical concerns.

The regulatory objectives of the Legal Services Act and the BSB and SRA handbooks govern conduct by lawyers, to act with integrity whilst protecting and promoting the interest of the client.

These regulations may soon insist upon an evaluation of success prospects using ROSS or RAVN. This may have the effect of weeding out so called ‘meritless applications’: ending the large-scale abuse of HMCTS’ services.

Rather than relying on lawyers to determine their chance of success, claimants will soon be able to rely on software that cannot have a vested interest in pursuing a case. Making and defending claims may be avoided if AI technology says it has no merit, reducing the need for any arbitration or litigation in defence.

The adoption of AI therefore, may have a revising effect on the duties of a lawyer, hurting profitability to begin with and may even threaten to wipe out any need for lawyers altogether.

McKinsey Global Institute found that currently 23 percent of a lawyer’s job could be automated and it can be presumed that this figure will gradually increase.

Early adoption of AI is likely be tentative and transitioning will be understandably harder in law, being a profession draped in heraldry and resistant to change.

These changes, however, do not spell doom for lawyers. Rather this is an optimistic projection for lawyers and society in general. As all industries strive for efficiency, so does the legal field, which has so far found a great friend in modern technology. It is likely that automation will replace stagnant jobs, only making the profession more productive and efficient.

In the way that MASS hospital has utilised AI in medical diagnostics is not seen as stepping on doctors’ toes but as an important advance in medical care, lawyers should adopt the same attitude as an opportunity to better their profession.

As faults are perfected, there will be a clearer case for lawyers to prioritise technology; if not as a helping hand for lawyers, then for the advancement of a more predictable legal system with better access to justice.

However, the fears that echo the Luddites grievances should not be dismissed outrightly as an illiterate response to inevitable change. Rather these grievances should serve as a marker signalling economic change.

Whilst Bill Gates’ recent suggestion to tax robots that replace human jobs does not stand up to economic scrutiny, it does identify the need to mitigate effects of AI on the job market.

Therefore, if technological developments are coupled with a political sentiment that is receptive to people’s needs, the bounty offered by these industrial developments can be shared more equally between more people than at any time in human history.

The Author

Jaskaran Singh Kohli is a UK-based businessman and is a founding partner at Chamberlain Legal and Professional Services, professional services firm specializing in legal services for individuals and small businesses, and VeenPool.io, a software agency focussing on Smart Contracts and Distributed Network platforms.

Article picture: The Leader of the Luddites, engraving of 1812. Source: Wikipedia