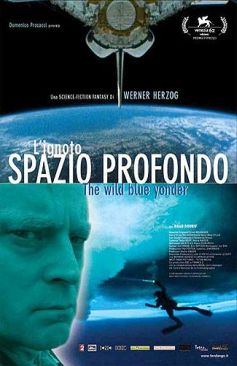

The Wild Blue Yonder

By Chris Middlehurst

Published on September 10, 2016

Imagine a film that mixes the rantings of a jet-lagged alien with video footage of a NASA mission to the moon, Ernst Reijseger’s screeching violins and underwater coverage of the polar icecaps. If you conceived this, you must be Werner Herzog, a very strange man who in each of your films infuriate, alienate and ultimately reward the viewer with a truly unique visual experience. Watching a Werner Herzog film is not so much like eating a box of chocolate as it is like finding a gooey mound in the park on a hot summer’s day that could be refreshing chocolate ice cream or… something else.

Either way, watching The Wild Blue Yonder, I never knew what I was going to get. Every shot that followed the last was unexpected, each storyline suddenly cut short by something else before re-emerging just when I thought I knew what was going to happen next.

How does one review a film like this? I can only tell you that I loved every minute of it and yet still don’t know what I have just seen or what I am reviewing now. Only Werner Herzog could have made a film like this that digests so many film conventions and then excretes them with such delight and gusto, throwing them back in the face of his shocked, startled and secretly delighted viewers. You know who you are. Like the best gooey mounds in the park on a hot summer’s day, this film shocks, delights, stinks, entertains and ultimately…works.

There are a few things I would like to mention about this bizarre and wonderful film: the editing and Brad Dourif’s mesmerizing performance as “The Alien.” Having googled the film, I realise that Joe Bini the editor has worked for Herzog on a number of other projects, including Grizzly Man and Little Dieter Needs to Fly. Bini also helped Lynne Ramsay unsettle viewers so effectively by toying with time and narrative structure in the 2011 domestic thriller We Need to Talk About Kevin.

Whilst the trickery involved in the joining of shots is the very definition of film itself, there is a special achievement to be appreciated in Bini’s success in merging shots so wildly different in subject and content into such a surprisingly cohesive whole: I imagine that the formatting of this film in merging grainy 35 mm film stock with shaky digital footage alone must have been a nightmare. Like the best editors, Bini is able to slip these technical puzzles into the background, letting the beauty and strangeness of the images themselves take over the editing.

And as for Brad Dourif, here is an actor who has been working for a long time in the movies, earning an Oscar nomination early on in his career as the tormented Billy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and cult fandom as a man trapped in a Chucky doll’s body. He has played menacing henchmen and oddballs on the margins of society for a long time, but here is given a superb opportunity to vent spleen on his baffled spectators. Dourif delivers what are essentially a series of rambling monologues glaring right into Herzog’s camera lens, eyes bulging and frothing rabidly at the mouth, surrounded by the destruction of earthquakes and the louring clouds of storms to come. Ade due dembella: the spirit of Chucky lives on.

The Author

Chris Middlehurst is The New Jurist film review editor. Chris graduated from Leeds University with a BA in English Literature, where he served as President of the LUU Film Making Society and also took elective modules in Chinese, Italian and World Cinema. He currently lives in Leeds and volunteers regulary at the wonderful Hyde Park Picture House, where he urges film lovers to visit if they get the chance!

Article picture: Wikipedia