The Heart as an Organ of Perception

By Charles B. Parselle

Published on February 17, 2012

Does a mediator need a heart? That depends on what you think a heart is for. Around the time the Mayflower set sail (1620s), the great Dr. Harvey made the discovery in London that the heart functions as a pump for blood. Until then, the teachings of the Roman physician known to us as Galen, who taught that the blood moved with a kind of pulse or wave motion, had been treated as the established orthodoxy for more than fourteen hundred years. Harvey’s discovery aroused such great consternation and hostility that one eminent physician remarked that he “would rather err with Galen than be right with Harvey.”

Ironically, modern research tells us that the heart is simply incapable of pumping blood through the 60,000 miles of blood vessels in a human body, and that Galen was partially right. Certainly the heart muscle functions as a powerful pump, capable of throwing a jet of water vertically ten feet into the air, but to pump two gallons of blood per minute through 60,000 miles of blood vessels would require a pump capable of throwing a 100-pound weight a mile into the air.

Further, Dr. Harvey knew nothing about electromagnetism, but today we know that the heart emits powerful electromagnetic impulses with every heartbeat, and is by far the most powerful such transmitter in the human body. For example, it is in this capacity 5,000 times more powerful than the brain.

Shortly after conception, the collection of cells that make up the beginnings of an embryo begin to pulsate, and those pulsations are electromagnetic. When two electromagnetic emitters come into contact with each other, their fields of energy interfere with one another and that interference is recognizable because it interferes with the wave patterns. This is the principle upon which a host of modern communication devices rely, for example radar, sonar and cell phones. Cell phones rely upon microwave transmissions but the principle is the same. The receiving organ picks up the transmission of the emitting organ and interprets it as a communication. Sound waves in the form of human speech are converted into microwaves that are transmitted from transmitter to transmitter and then converted back into sound waves to be received by a human ear, and the human brain then interprets those noises as speech having a certain meaning.

The heart functions in the same way. The developing embryo perceives nothing but the steady heartbeat of its mother. The embryonic heart develops long before the embryonic ear, which hears first only the rush of blood, but the developing embryo starts to interpret the mother’s heartbeats, and those electromagnetic transmissions are interpreted as emotions. The four principle emotions are sad, mad, glad and scared, just as the four basic tastes are sweet, sour, bitter and salt, but from these simple bases we combine and interpret an enormous range of information. We can affirm that the heart is an organ for pumping blood, but also a transmitter and interpreter of emotional states.

Although our science has been slow to recognize the heart as an organ of feeling and perception, our language is in no doubt. Consider the plethora of heart-based expressions in English usage: heartfelt, from the bottom of my heart, I wish with all my heart, with heart and soul, heart-stricken, heartsick, heart-rending decision, heavy-hearted, lighthearted, with an innocent heart, a black-hearted villain, the heart has its reasons that reason cannot comprehend, our hearts are joined as one, I heartily agree, and so on. And we talk about hunches, female intuition and gut instinct.

When we consider our role as mediators, we must wonder what we can bring to the table that the parties do not already possess for themselves. We usually provide a space for them to sit and a cup of coffee, but then what? Some of us may offer suggestions, but can all of us say that we are likely to prove better problem-solvers than the parties themselves? Often parties are represented by attorneys, who are trained problem-solvers, and everyone present in the room knows a hundred times as much as the mediator will ever know. They have often been living with their mutual problem for a long time, and the files they have built up are voluminous.

The mediator is not asked to read those files from beginning to end. The mediator can have no more than a rudimentary knowledge of the details of the dispute in which the parties have been engaged for so long. It is a little presumptuous to expect that the mediator can read a brief, listen to the various communications for several hours, and come up with a satisfactory solution, and indeed we do not do so. We expect the parties to resolve their own dispute, and we claim to be “facilitating” the process or providing a “safe space” in which they can interact.

But what does it mean to provide a safe space? They could as easily go to a hotel and sit in the lobby, or meet at the courthouse, which is protected by armed guards. I suggest that what makes our space “safe” is the influence of our own personality, and our own personal ability to help each party think or feel their way towards a mutually satisfactory conclusion. Of course I do not say that it is simply a matter of breathing deeply and smiling. Our mediator mind is also engaged, but our society is not lacking in problem-solving ability. It is lacking in heart. As a culture, our hearts are uneasy, which is why diseases of the heart are the commonest cause of death.

Probably this is the reason why mediation exists at all as a profession. It is to provide something that in our present society is in short supply.

Is it possible to cultivate the heart as an organ of perception and understanding? I suggest it is not only possible but also absolutely necessary. Even the most hard-boiled “mentals” will notice the difference even if they cannot quite explain what it is.

The Author

Charles B. Parselle is a mediator, arbitrator and attorney. He graduated from Oxford University’s Honor School of Jurisprudence and is a member of the English bar, then joined the California Bar in 1983. A prolific author and sought-after mediator, he is the author of the book, “The Complete Mediator.”

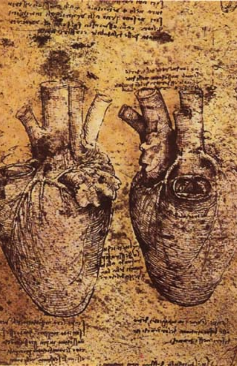

Article picture: A painting by Leonardo Da Vinci. Source: Wikipedia