The Best Candidate for the Toughest Job

By Kofi Annan

Published on October 18, 2011

In December this year, a little-reported process will conclude when those 119 States who are parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) elect a new Prosecutor. There are many important decisions facing the world’s diplomats, including those gathered at the UN General Assembly this autumn, but though little-noticed this decision is no less momentous. The process must result in the appointment of the most qualified candidate, and not, as is too often the case when top international jobs are filled, the person thought least offensive to the most countries.

The ICC Prosecutor and the office he or she presides over carry a heavy responsibility – to bring to international justice the perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. Of course, the Prosecutor acts within the confines of the Rome Statute – only pursuing cases where states fail to do so, or where the states themselves, or the UN Security Council, refer situations to the Prosecutor. To open a case, the Prosecutor must convince the judges in pre-trial proceedings that he or she has sufficient grounds to do so.

In the last several years, we’ve seen how important this role is: pursuing criminal warlords in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda. And also how difficult: prosecuting political leaders in the Sudan, Kenya and Libya.

Some political leaders, including those who risk prosecution, are openly and maliciously challenging the impartiality of the Prosecutor; others refuse to abide by their obligations under the Rome Statute to co-operate fully with the Prosecutor so that investigations, indictments and trials can proceed.

And many powerful states, including China, Russia and the United States, all permanent members of the Security Council, have still not joined the court, even if they are now less vocal in opposing it.

Clearly, the Prosecutor has a tough job. He or she must stand with the victims and pursue justice, but do so in a way that demonstrates to all fair-minded people that the law is being applied equally without bias or favour. No easy task in a world where trust is in short supply. He or she must rely on governments to make justice real – there is no international police force. Legal knowledge is key, as is a devotion to justice and the ability to lead an international team effectively. The Prosecutor must, above all else, have the skill to build, pursue and win cases, while deftly maintaining the confidence of both victims and governments.

The Rome Statute recognises that this is a unique international post. The Prosecutor serves for up to nine years, and cannot be re-elected – thus strengthening the independence of the post. Moreover, unlike many senior international posts, there are very specific and clear rules in place to prevent the arbitrary removal of the Prosecutor. The Rome Statute also makes clear that appointment should be solely on the basis of merit and proven experience, and that whoever is chosen must be a person of “high moral character”.

The 119 States that have so far joined the Rome Statute are obliged, therefore, to avoid the temptation of treating this appointment as they do other international jobs. Too often, candidates for senior posts at international organizations conduct elaborate election campaigns in conjunction with their governments. This approach brings quite a lot of problems with it: first, persons who are not supported by their own governments, no matter how qualified, have no hope of becoming an official candidate, much less getting elected. It also leads to vote-trading in a type of global bazaar: one country promises support for another country’s candidature in exchange for the latter’s support for one of its own candidatures for a different post. Merit often becomes a secondary consideration.

This must not happen in the election of the ICC Prosecutor. There must be no hint of politicking in the election of the person who will exercise the important functions assigned to this post.

To their credit, the States Parties to the Rome Statute are trying something new. A Search Committee with five members has been constituted to search for possible successors to the current Prosecutor. The Search Committee has drawn up a list of candidates all of whom will be interviewed, and then it will provide the States with a final short list of three names. The final decision rests with States. Member States may still nominate separate candidates, but so far none of them have done so, thereby respecting the Search Committee process.

This process is highly unusual in the international sphere and deserves the full support of all those interested in the success of the ICC. It holds out real hope of producing a consensus candidate who is chosen because he or she is best equipped to do the job. And it is this, above all else, that must guide the final decision in December.

When as UN Secretary-General I opened the Conference in Rome 1998 where the ICC Statute was being drafted, I urged the delegates “… not [to] flinch from creating a court strong and independent enough to carry out its task. It must be an instrument of justice, not expediency. It must be able to protect the weak against the strong.” This was accomplished in Rome. The ICC Statute is a remarkable achievement.

But politicizing the election process for the Prosecutor, or polluting it with the horse-trading and vote-swapping that characterize too many elections for international and UN posts, would risk undoing this important achievement.

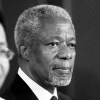

The Author

Kofi A. Annan was the seventh Secretary-General of the United Nations, serving two terms from 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2006.

Article picture: ICC building. Picture by Vincent van Zeijst. Source: Wikipedia