Making Human Dignity Central to International Law

By Matthew McManus

Published on March 24, 2017

Abstract

This essay attempts to sketch out such a moral conception that is both attractive and adaptive to the needs of international law as it exists in practice. I will argue for adopting a Kantian position that sovereignty itself should be conditional on sovereign states maintaining a “rightful condition” for the positive development of all people living within that territory which maintains respecting human dignity as the central ideal of law. The requirements for maintaining this “rightful condition” would include codifying a system of rights at the international level which all states must become party to and embody in their own domestic legal systems.

Introduction

Defending a moral conception or international law poses a significant challenge. One must show how such a conception can be applied rigorously and adaptively to the unique conceptual and practical problems posed by international law. Moreover, they must demonstrate that a full international legal system, if fleshed out with all the sources of power needed to make it effective, would not be an undemocratic force in the world. Instead, it would be one that amplifies individual self-authorship and links that to a conception of state legitimacy.

I will only be able to sketch out how international law can contribute to maintaining such a “rightful condition” by amplifying human dignity. But I hope to show that the conceptual links can be drawn, and that the model proposed is attractive from a moral point of view.

I will begin by clarifying that my conception of dignity is highly individualistic, and relates to a person’s general capacity for self-authorship. I believe that an individual has dignity to the extent they are capable of transforming the world around them, and therefore defining themselves through this active engagement. If individuals are able to become authors of their lives in this substantive way, we can say they have lived a dignified life.

Archetype of Law

The argument presented here is, in many respects, deeply Kantian. Our basic dignity, as Kant understood it, lay in our existing as transcendental beings that ascribe value to the world rather than having value immediately ascribed to us externally by nature. Because we care about the existential world we inhabit, we constitute the ends we wish to strive for and in so doing establish the boundaries that will have to be transcended to achieve those ends. However, I believe we must go beyond Kant in establishing that dignity has an inherently social dimension. This is why we must understand that self-authorship is integrally linked to an individual’s capacity to transform the world around them. We cannot simply look at what overt constraints are imposed on individuals. The dignity of individuals is not entirely respected when legal and political institutions simply avoid interfering with the lives of their citizens except where their actions infringe on the rights of others. If dignity is related to self-authorship, we must also look at what individuals are actually capable of doing.

Dignity, I will argue, is respected when legal and political institutions establish equal conditions for all individuals to prosper or fail and have their claims acknowledged or dismissed in the self-authorship of an authentic life. For states to respect it, they would need to do much more than simply refrain from certain actions. Respect for human dignity would entail codifying and respecting a set of positive rights that would make individuals more capable of self-authorship. If states did so, they would make respect for human dignity the unifying ideal of law by working to establish the rightful condition for individuals to be capable of authentic authorship of their lives.

Making human dignity the unifying ideal of law would be most easily done through international and human rights law. There are already a substantial number of legal decisions and scholars who have demonstrated how it can be made the unifying ideal.

Justice Aharon Barak has helpfully described such a process in his book Human Dignity: The Constitutional Value and the Constitutional Right. Here dignity plays the role of a “mother right” which births a number of “daughter rights” through a process of interpretation. Through this process we move from respecting human dignity at an abstract level and come to respect it as constitutive of more specific rights with legal force enacting them.

“A constitutional right formulated as a principle serves as a ‘common roof’ under which a wide variety of situations crowd together. Common to all of them is that they are expressions of the general principle that shapes the right…Under the canopy of the constitutional framework right, constitutional rights derived from it or that radiate from it crowd together. These rights are inherently of a lower level of generality than the framework right…A framework right is therefore a mother right. From it are derived daughter-rights. If the daughter-rights themselves are framework rights at a lower level of generality, granddaughter-rights are to be derived from them. Other imagery expressing this concept views the mother right as a tree and the daughter rights as branches growing from it.” – Justice Aharon Barak

Archetype of Law

Another way of expressing this same point would be to see the protection of human dignity as the, not merely a, fundamental constitutional “archetype.” A states’ commitment to protecting and realizing this archetypal right should influence the hermeneutic production and interpretation of any code of law.

If my model were accepted, and dignity taken as the unifying ideal or archetype of law, it would have significant ramifications for our understanding and justification of sovereignty. The moral respect we show to human dignity could be hermeneutically linked to subsequent and increasingly more specific moral commitments codified in human rights documents, such as those required to democratically legitimate the state and those required for the full development of the human personality. Ideally, over the course of time the link between domestic and international law would gradually become blurred as states internalize the democratic and economic requirements for sovereignty and regard them as integral principles underpinning their own legal systems. International human rights law would then overlap with domestic law in a self-reinforcing manner as states increasingly affirm international law as a matter of principle rather than simply as a positive legal requirement. This would, in turn, establish a mutually legitimizing chain through which both domestic and international legal systems validate their position relative to one another.

The Result

As human dignity becomes the legitimating ideal through which states claim the moral authority to govern because they establish the “rightful condition” for their citizens, they can only retain this authority by realizing the ideal through concrete legal practices that respect human rights. Where they fail to do so, we can say that states will be in violation of international human rights law and that, if they fail to rectify the situation, they will gradually cede certain sovereign powers. Through this process, the rightful condition could be established in rights-respecting states. Moreover, international law would both overlap with domestic law and serve as an antidote to the abuses of sovereign authority.

The Author

Matt has a Ph.D. in Socio-Legal Studies and is currently completing his Post-Doctoral research on low-income families in Toronto. His academic interests include human rights, international law, and political/legal theory. He can be reached via email at garion9@yorku.ca

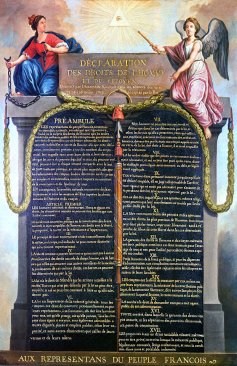

Article picture: Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen approved by the National Assembly of France, August 26, 1789. Source: Wikipedia. Article picture no.2 by Conchirevu via Pixabay