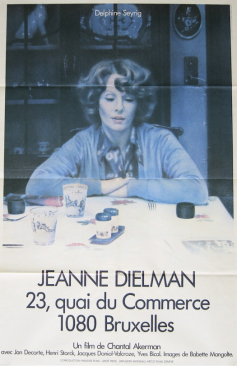

“Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles”-Chantal Akerman (1975)

By Chris Middlehurst

Published on November 3, 2016

When asked who he was, Charles Manson pulled a few faces and whispered: “I’m nobody. I’m a tramp, a bum, a hobo. I’m a boxcar and a jug of wine. And a straight razor if you get too close to me.” I include this chilling quote here because, in some way, it is comforting: we can see the madness behind the words and the mind of a man on another plane of existence, who found it necessary to organize the butchering of innocent people in cold blood. But in Chantal Akerman’s colossal, 3-hour plus epic, Jeanne Dielman is different: there are no such revelations of her inner being. No one ever even asks who she is. This, along with Taxi Driver, is one of the most uncomfortable portrayals of human loneliness that I have seen. It is painful to watch. Like all of us, Jeanne fills her time as best she can: she goes on trips to the post office, cooks dinner for her son, and occasionally entertains the odd male customer. Only then do we sense what she does for a living. But there is nothing that she seems to enjoy, nothing she has a passion for, no way into her mind, even though we seem to see her do everything. The ritualization of daily activity by Akerman and Delphine Seyrig, whom Akerman cast primarily because she seemed so aloof and above such daily chores (and would therefore seem more interesting performing them) casts a new light on activities such as listening to the radio or switching a light on and off. The everyday monotony of existence and the performance of minute tasks is made magical, alien and surreal. Days after the film ended, there was not a single vegetable I could peel or a coffee I could make without thinking of Jeanne Dielman sitting so totally alone in her apartment, cut off from the rest of the world.

I recently saw an interview with the film’s director, Chantal Akerman, who sadly committed suicide last year shortly after the release of her latest documentary, No Home Movie. She comes across as a warm and charming person, full of life and happiness, the exact opposite of Jeanne Dielman. Yet we sense that she understands and has compassion for her protagonist, so much so that she devotes over three hours of screen time simply observing her because no one else will. Akerman has the compassion and kindness to give Jeanne Dielman the time of day: her camerawork is static, observant, never panning or gliding to anything else that might distract or divert us. Shots are often repeated, albeit with minor alterations, usually in Delphine Seyrig’s hand movements. Some would say that less is more. Watching Seyrig, I would conclude that less is less is less is less.

Chantal Akerman proves with Jeanne Dielman that she is a gifted hypnotist: we watch her watch the colour of coffee changing with milk or watching the traffic lights bounce off her bourgeois apartment walls. We see her scrub a bathtub until it shines. We witness her waiting patiently for the lift to come. And yet by the final credits we still don’t know who she is. Akerman’s subject is, like Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, a ticking time bomb. A three hour and twenty minute one, but a ticking time bomb nonetheless.

The Author

Chris Middlehurst is The New Jurist film review editor. Chris graduated from Leeds University with a BA in English Literature, where he served as President of the LUU Film Making Society and also took elective modules in Chinese, Italian and World Cinema. He currently lives in Leeds and volunteers regulary at the wonderful Hyde Park Picture House, where he urges film lovers to visit if they get the chance!

Article picture: Wikipedia.