History of Burglary

By Ben Darlow

Published on May 20, 2014

Burglary is a crime which has changed significantly over the years but in all its forms has always reflected the seriousness of breaking into a building, or part thereof, and the damage that can cause to both people and property.

In Anglo-Saxon times, the then equivalent of Burglary was known as husbryce which literally meant ‘house-breach’. However, its definition was geared more towards a person having caused injury to another in the process of an armed raid on a town.

Up until the mid-15th Century, breaking into a building does not appear as a separate offence in itself, it only appears in the courts as an aggravating factor. It could turn a petty theft into a felony for which you could be sentenced to death.

By the 1450s, Burglary appeared as its own offence and could be committed even if nothing had been stolen from the building, all there needed to be was an intent to steal something. It was at this time that the offence first started to be known as Burglary, rather than house-breaching/breaking or criminal invasion of a building.

Burglary of the 15th Century had two elements that seem unusual to us now. Firstly, it was an essential requirement that someone was in the building at the time the burglary took place and secondly, the burglary had to take place at night. If a de facto burglary was carried out in the daytime, it would only be trespass at common law and not a felony offence.

The second element led to some interesting judge discussion on what constituted night. Originally, a 1505 case set the definition as after sunset and before sunrise but this led to people being able to commit Burglary in twilight conditions. This lasted until a case in 1606 where judges set the test of whether a man’s face was discernible.

In 1837 a definition of night was made so arbitrary that it could be proved in any case but it was not officially repealed until the Theft Act 1968, where the nocturnal element was finally abolished from Burglary. The requirement of someone being in the building at the time of the Burglary had been abolished earlier with several statutes beginning in 1547.

The current law on Burglary is to be found in ss. 9 and 10 of the Theft Act 1968. Section 9 lays out two species of burglary that can be committed, s.9(1)(a) is where a person enters the building, or part thereof, as a trespasser with intent to commit theft, GBH or criminal damage to the building and s.9(1)(b) is where a person enters the building, or part thereof, as a trespasser and actually commits theft or GBH. A person can be sentenced to a maximum of 14 years in prison for a s.9 burglary.

Section 10 lays out a new offence of Aggravated Burglary where a person commits burglary whilst carrying a firearm, imitation firearm or certain weapons of offence defined in the section. This offence carries a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.

The Author

Ben Darlow is the author of the English Legal History blog and has an LLB (Hons) Law degree from the UK’s University of Leicester.

He has always had a healthy academic interest in, and fascination with, Legal History and established the English Legal History blog in April 2013 to bring that interest to a wider audience in an easy-to-digest and accessible format.

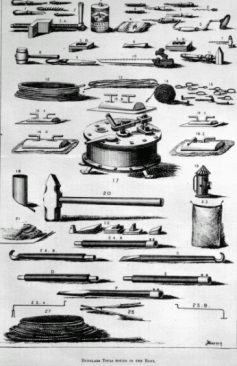

Article picture: Burglars Tools Found in the Bank. Source: Wikipedia