Gandhi, Mandela and King: The Trinity of Nonviolent Civil Resistance

By Joseph Kaifala

Published on June 11, 2016

In December 2010, a popular protest erupted in Tunisia and spread across North Africa and the Arab World. These popular protests, collectively referred to as the Arab Spring, ignited regime change in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and other countries in the Arab World. Although the popular uprisings were activated by minor protests, the succeeding revolutions were brewing for a long time in the hearts of many. The leaders who were removed from power had been in office for decades, but failed to strengthen democratic freedoms and cater to the basic needs of their people.

Some commentators now question the successes of the Arab Spring, given that Libya is still at war and Egypt has not yet discovered a clear path towards democratic governance, but it is the idea of nonviolent mass protests against previously insurmountable regimes on the African continent that is worth celebrating. The popular overthrow of tyrants such as Gaddafi, albeit in what ended up becoming a rather violent conflict, sent a message to other African leaders that no regime, no matter how strong, can defeat a people who collectively say enough is enough.

In October 2014, the people of Burkina Faso said enough is enough to former President Blaise Compaor who had been in power for twenty-seven years. They forced the previously têtu president out of office through a series of unrelenting protests. Over recent years we have also witnessed popular protests in places like Guinea and Ivory Coast that led to regime change in those countries. As many Africans continue to live under leaders who delay their democratic process by clinging to power, Nonviolent Civil Resistance has become the only democratic tool left to the people to take back their governments. The concept of Nonviolent Civil Resistance originates in the satyagraha (nonviolent resistance) movement of the Indian Mahatma, Gandhi, during his work against racial discrimination in South Africa and the Indian Independence struggle. Gandhi’s method of Nonviolent Civil Resistance was later emulated by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. during the American Civil Rights Movement and Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC) during the South African struggle against apartheid. As Africans continue to use Nonviolent Civil Resistance to pursue sociopolitical change, it is important to reexamine the different ways in which these three pioneers used it to effect change.

Mahatma Gandhi, who may be referred to as the godfather of contemporary Nonviolent Civil Resistance, based his practice on relevant doctrines of his Hindu religion. A foundational principle of the Gandhian Nonviolent Civil Resistance was ahimsa, nonviolence towards all creatures. According to Gandhi, a votary of ahimsa remains true to his practice if all of his actions are rooted in self-restraint and compassion; that is, to shun to the best of his ability the destruction of any life. Ahimsa therefore requires the Satyagrahi to practice the utmost civility, which Gandhi described as an inborn gentleness and desire to do the opponent good. Based on these principles, Gandhi’s version of Nonviolent Civil Resistance rejects all forms of violence on the part of the Satyagrahi and promotes unconditional love for the opponent. As he put it, Satyagraha is an absolutely nonviolent weapon. And this commitment must hold true in thought, word and deed.

The requirement of unconditional love even for the opponent was entrenched in Gandhi’s belief that we are all good, though our actions sometimes betray our true nature. He believed that man and his deed are two distinct things that could be isolated in order to reform the person. As he explained, whereas a good deed should call forth approbation and a wicked deed disapprobation, the doer of the deed, whether good or wicked, always deserves respect or pity as the case may be. In other words, hate the sin and not the sinner. Rather unfortunately for the Satyagrahi, the opponent sometimes responds in unequal measures, inflicting unflinching violence on nonviolent citizens.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. adopted Gandhi’s Nonviolent Civil Resistance methods in his leadership of the American Civil Rights Movement. He studied Gandhi and made a pilgrimage to India in order to better understand Gandhi’s movement. As a reverend, the idea of absolute nonviolence was in conformity with Jesus’s teaching in Mathew 5: 39-40, which states that whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other too. And if a man will sue thee for thy coat, let him have thy cloak too. In tandem with the principle of ahimsa is the Christian value of love as the greatest commandment. As Dr. King put it, I had come to see early that the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to the negro in his struggle for freedom. Even though pockets of the Civil Rights Movement suggested retaliatory violence in response to police brutality and other hate crimes, Dr. King insisted that nonviolence is a way of life and not merely a tool of convenience.

In February 1959, Dr. King and a few other leaders of the American Civil Rights Movement embarked on a pilgrimage to India in order fully understand the concept of Nonviolent Civil Resistance. During this trip, Dr. King was confronted with the question of whether Nonviolent Civil Resistance is effective in situations where the campaigner does not have a potential ally in the conscience of the opponent. In response, Dr. King argued that true Nonviolent Civil Resistance is not an unrealistic submission to evil power, but rather a courageous confrontation of evil by the power of love, in the faith that it is better to be the recipient of violence than the inflicter of it, since the latter only multiplies the existence of violence and bitterness in the universe, while the former may develop a sense of shame in the opponent, and thereby bring about a transformation and change of heart. This view explains the ultimate aim of Nonviolent Civil Resistance, which is to change society for the better, rather than serve the evildoer in equal measure of evil. A successful nonviolent campaign, as Dr King perceived it, should lead to redemption and the creation of a better community.

The African National Congress in South Africa remained committed to absolute nonviolence, but Nelson Mandela was later compelled by the circumstances of his campaign against apartheid to take a hybrid approach to Nonviolent Civil Resistance. Where Gandhi and Dr. King saw Nonviolent Civil Resistance as an inviolable moral tool for the oppressed to use against their oppressor, Mandela viewed it as a tactic to be employed when necessity demands it. Mandela believed that the actions of the oppressor both in India and the United States were sometimes checked by established laws and public opinion, but the apartheid regime in South Africa was determined to retain power at all costs. It had no conscience.

Mandela founded Umkhonto we Sizwe, the militant wing of the ANC, because he believed that the time had come to either submit to violent white supremacy or fight. He held the conviction that no leader should deliberately lead his people down an abyss. The reasoning behind Mandela’s decision is best described in the first interview he gave from underground. According to him, there are many who feel that it is useless and futile to continue talking about peace and nonviolence against a government whose only reply is savage attacks on an unarmed and defenseless people. The purpose of Umkhonto we Sizwe was not, as Mandela put it, to chase whites into the ocean, but to make South Africa a home for all who live there. In order to avoid a retaliatory racial conflict, Mandela chose sabotage as a strategy to prevent civilian casualty and force the government to negotiate a peaceful end to the conflict. Government infrastructure was usually targeted at night when workers had already left for the day. The aim was to cripple the government to the point that it would have had no choice but to negotiate. Ultimately, what Mandela sought was not a violent revolution, but rather an opportunity to compel the apartheid regime to the peace table.

In spite of the various ways in which these leaders used Nonviolent Civil Resistance, what they had in common was love for their people. While Gandhi and Dr. King would have never resorted to any form of violence, Mandela believed the apartheid system was so devoid of conscience and scrutiny that to lead his people to confront such a morally bankrupt system without countermeasures would have been suicidal. The lesson for a new generation of Africans interested in using Nonviolent Civil Resistance is that the concept primarily requires committed leaders who inspire their people to love. A successful Nonviolent Civil Resistance campaign leads to a peaceful negotiation to resolve the bone of contention, leaving all parties with a dignified outcome. A Nonviolent Civil Resistance campaigner does not see the other party as an enemy, but rather as a misguided opponent who could be persuaded to change for the good of all.

What confronts Africa today is not the yoke of colonialism or imperialism; it is a failure of leadership that limits the continent’s potential. Confrontation with these regimes, usually armed to the teeth, will require a resort to Nonviolent Civil Resistance. In any democratic system, power resides with the people, and their government, no matter how strong, cannot defeat a people yearning for change. In such struggles for change, citizens will sometimes face regimes that speak only the language of violence, but the moral supremacy of Nonviolent Civil Resistance ultimately prevails over the most potent weapon.

The Author

Joseph Kaifala is founder of the Jeneba Project Inc. and co-founder of the Sierra Leone Memory Project. He was born in Sierra Leone and spent his early childhood in Liberia and Guinea. He later moved to Norway where he studied for the International Baccalaureate (IB) at the Red Cross Nordic United World College before enrolling at Skidmore College in upstate New York. Joseph was an International Affairs & French Major, with a minor in Law & Society.

He holds a Master’s degree in International Relations from the Maxwell School at Syracuse University, a Diploma in Intercultural Encounters from the Helsinki Summer School, and a Certificate in Professional French administered by the French Chamber of Commerce.

Joseph was an Applied Human Rights Fellow at Vermont Law School, where he completed his JD and Certificate in International & Comparative Law. He is recipient of the Vermont Law School (SBA) Student Pro Bono Award, Skidmore College Palamountain Prose Award and Skidmore College Thoroughbred Award.

Joseph was a 2013 American Society of International Law Helton fellow. He served as Justice of the Arthur Chapter (Vermont Law School) of Phi Alpha Delta Law Fraternity International. He is a member of the Washington DC Bar.

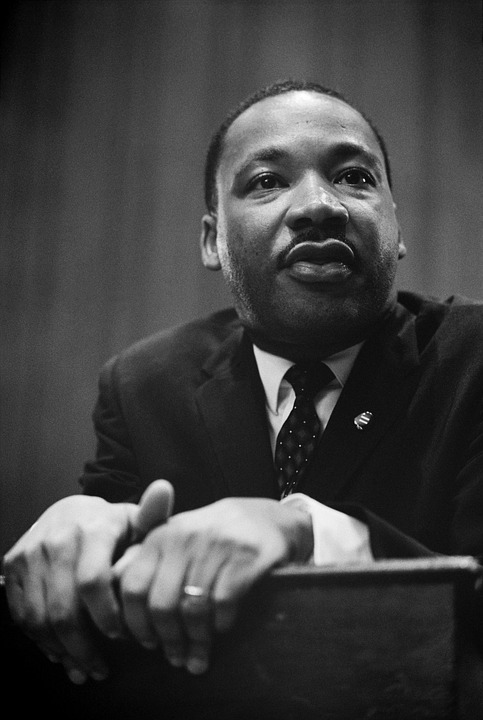

Article picture: Martin Luther King, Jr. Source: Wikipedia