Exposing the Jury: Making Jury Duty More Appealing Through Film

By Joseph Kaifala

Published on August 24, 2013

I have yet to meet a single person who rejoices over a jury duty summons. Democracies spend enormous resources preparing and encouraging citizens to participate in governance through civic duties such as voting or running for public office, but one hardly hears about an organization devoted to explaining jury duty and the weight of that responsibility in a democratic system. The jury system has always provided a channel through which ordinary people participate in the application of law and order and the overall process of the rule of law. However, unlike other mechanisms such as the right to vote, which sometimes requires people to spend a whole day in line to cast their ballot, jury duty is a bigger burden on popular mindset. It is something nobody wants to do, but no one can really explain why this aspect of political participation appears more burdensome than say filing taxes.

In Magic In The Movies-Do Courtroom Scenes Have Real-Life Parallels?, Judge Patricia Marks exposes some of the excuses made by potential jurors to avoid jury duty in movies and how that translates into real-life excuses. She highlights some examples of excuses such as the New York City news anchor who arrived for jury duty wearing a NYPD t-shirt and carrying a beach chair and a portable radio; a juror who complained that he could not make it to court because his jury duty summons was taken by aliens; another whose cat had kittens and she wanted to stay home for six weeks; and a man in the process of changing his gender who wanted to know whether he should go to court as a man or woman.1 These are just a few examples she offers, but one can presume that court clerks receive even sillier and more imaginative excuses from people who are frequently attempting to garner reasons not to perform jury duty.

Popular culture, especially media portrayal of the legal system, is very important to the understanding of law by lay people. Most ordinary views about lawyers have been crafted in popular culture through the media, especially courtroom movies. Ideas of the greedy, heartless, and miserable lawyer emanate from popular movies about the law. The occasional morally correct and ethically sound lawyer who seeks either self-redemption or societal interest is thrown in to restore some faith in the functioning of the third branch; otherwise there is a risk of destroying all faith in the tribunals of justice. When the jury appears in films and in the media, generally, it is usually in either one of two roles: either for reaching an “erroneous verdict” as a result of their alleged incompetence or for awarding “excessive damages” for so-called emotional or sentimental reasons.

According to Nancy Marder, “[i]n press coverage, criminal juries have been faulted for reaching erroneous verdicts and civil juries have been chastised for awarding excessive damages.” She further states that the press typically attributes what it perceives as an erroneous verdict to bias or sympathy, and the awarding of excessive damages to sheer incompetence or sentiments.

Therefore, the message most ordinary people receive about the jury is that they are a bunch of incompetent people who award excessive damages out of emotional reaction to courtroom tales. Marder states that “[w]hat is lost from public consideration is the way the jury works properly in the myriad of jury trials that never find their way into press stories.” As a result of this dearth of information in popular media about the gravity of jury duty and the enormous weight on the shoulders of most jurors, “[p]ublic disenchantment with the criminal justice system increasingly centers on the jury;” the men and women who must convict or acquit.

Approximately 1.2 million people participate in jury deliberations in the U.S. each year and generally reach verdicts most presiding judges view as accurate6, but it is perhaps the invisibility of jury deliberations that makes many people view their role as damaging to the justice system.

According to Carol Clover, “[t]he first and most important thing to be said about trial-movie juries, then, is that they barely exist. In the courtroom, juries are seen only briefly, and the work they do, their deliberation, is with very few exceptions avoided altogether.” If what we see is either a hung jury, a jury that renders erroneous verdicts because they do not understand the laws they apply out of incompetence, or a jury that sympathetically offers excessive damages, then we are forced to conclude that the jury is responsible for the flaws of the justice system.

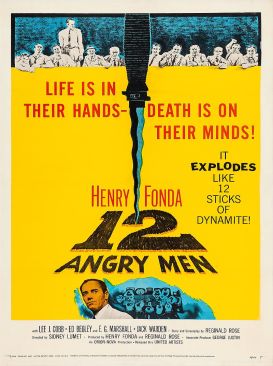

Nobody becomes excited about a system they do not understand (unlike other courtroom activities which are open to the public, jury deliberations happen behind closed door) and probably view as flawed and corrupt. However, according to Lisa Kern Griffin, “[t]he jury system lies at the heart of our democratic system, but it has lost much of its moral authority in the popular legal culture.” And as Carol Clover puts it, the “habit of avoiding the jury may seem a little odd in light of our public commitment to the institution and also in light of ongoing discussion about its value.” This is why movies such as 12 Angry Men, The Verdict, and the BBC drama The Chatterley Affair, are important to exposing and redeeming the jury system.

Of the three films, 12 Angry Men is probably the one that grants significant value to role of the jury in Western legal systems. Twelve men are summoned to serve as jurors in a murder trial. These ordinary men of different professions and qualifications are placed in a cramped and uncomfortable New York City courtroom and told to do what jurors do at trial: to convict or acquit. In fact, the judge in this case elevates the role of the jury to a much higher moral pedestal by instructing them that their duty is to separate “facts from fancy.” This statement alludes to the popular view of the courtroom as a place where truths and lies clash, and a third party (the jury) is needed to rescue the truth from the facts and fancy.

But more importantly, the judge heightens the enormity of their task by reminding them that “one man is dead; another man’s life is at stake,” and if they render a verdict of guilty, there will be no mercy because the death penalty is mandatory. This information goes to show that the jury must take its role seriously because error might be costly for the defendant. He concludes by pointing out that they are faced with a “grave responsibility.”

The warning in 12 Angry Men pertaining to the grave responsibility of jurors is in contrast with the representation of jurors in most contemporary courtroom movies. One is used to seeing a silent bunch to whom lawyers deliver their arguments. In this regard, the jury in most popular films is a prop rather than a pertinent part of the whole system of justice. The most important aspect of 12 Angry Men is that it is a film entirely dedicated to jury duty; as a result the rest of the movie is devoted to exposing the most hidden aspect of jury duty—the deliberation. Like most people today, they enter the deliberation room with predetermined ideas of getting out of there as early as possible; hence the surprise to see the door locked and the ball tickets for the evening game one of them carries. This is why Nancy Marder says, “[o]ne way to understand 12 Angry Men is to see it as a movie about the transformative power of jury deliberation.”

However, even the jury in 12 Angry Men approaches their duty with an initial lack of interest or commitment. It sufficed to cast a ballot and go home, until jury number one decided that the weight of the duty was too important to be determined by mere votes without talk. Jury number one justifies his request to talk by stating that “it’s not easy to raise my hand and send a boy off to die without talking about it first.” In his mind, unlike electing a senator, which one can do without much ado and the democratic system wouldn’t crumble; sending a person to hang requires some deliberation, because an error of judgement is irreparable. It is a process which unlike elections is not contested and revalidated every few years.

The rest of the movie unfolds with a proper deliberation and the testing of truths and untruths, assumptions and prejudices. According to Bill Nichols, 12 Angry Men “dignifies the principle of the jury as buffer and of the arduous process of consensus-building as its central theme…” and “Fonda embodies a spirit of doubt aligned with the higher truth of justice and the spirit, not the letter, of the law.” Therefore, what the personalities and deliberation in the 12 Angry Men represent is the diversity of interest that underlies the spirit of the law as compared to the strict autonomy of the letter of the law which is represented by lawyers and judges who may not be familiar with the societal idiosyncrasies beneath the stories they present in court.

The Chatterley Affairs is a BBC drama pertaining to the scandal surrounding D.H. Lawrence’s controversial novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The film explores the landmark 1960 obscenity trial to determine whether to ban the book. The film is very similar to 12 Angry Men in the way jury duty unfolds through deliberation. The judge orders the jury to read the book in court and decide whether it should be banned. Unlike 12 Angry men, the personality differences are not based on profession and sense of duty, but rather on age, class, and gender. There were two women and three relatively young people on the jury in The Chatterley Affair.

The Chatterley Affair shows the diversity of the jury through the clashes and arguments that unfold around interpretations of the book. Keith and Helena, two members of the jury decide to try all the sexual acts in the book before deciding whether to ban it or not. The older members of the jury think there is no point going on about the “dirty bits” except to get people “feeling fruity.” To older members of the jury, it is simply a “dirty book.” But Helena reminds them that “it is only a book afterwards…I mean books can’t harm you, can they?” In fact, this is the very issue they were called to decide. In 12 Angry Men, ordinary men are called to determine whether another member of their society should hang for murder. They use their experiences and understanding to deliberate the question. The jury in The Chatterley Affair is called to examine and shape their society by deciding whether the book in question can deprave and corrupt.

The jury is seen as a rough sample of society who has a stake in the outcome of decisions affecting that society. The prosecutor, defense, and presiding judge in The Chatterley Affair portray the jury as the highest arbiters of justice. Only the jury can transcend the ‘fancy’ and draw reasonable conclusions from facts. In the end, the judge places them above the multitudes of experts who testify at trial. From the perspective of the defense, the jury is a good sample of society with authority to influence the progress of their society. He asks, “but isn’t everybody, whether earning 10 pounds a week or 20 pounds a week, equally interested in the society in which we live, and equally involved in the problems of relationships, including sexual relationships, and shouldn’t wives be allowed to read about these things, as well as their husbands, and isn’t it time we rescued Lawrence’s name from the quite unfair reputation it has had, and allowed our people, his people, to judge for themselves?”

“Members of the jury, I leave Lawrence’s reputation and the reputation of Penguin books, in your hands.”

The prosecutor also closes by emphasizing the role of the jury as guardians of the morals of society and judges of facts. He calls on them to “judge this as ordinary people, with your feet firmly on the ground, reading this book and judging it according to your own standards of morality…remember that you and you alone are the sole judge of the facts in this case.” In the end, the presiding judge gives a final jury instruction that reiterates the role of the jury as judges of facts and superior examiners of expert testimonies. He states, “members of the jury, you are the sole judges of the facts. As we all know, these days the world seems to be full of experts, but our criminal law is based on the view that the jury thinks of the facts and not the view that the experts say you should take. You’ve got to look at the book as a book that you yourself might have bought for 3 shillings and 6 pence at the bookstore and then you must ask yourself the question, did it tend to deprave and corrupt…if you have any reasonable doubt whether it’s been proved to your satisfaction that the tendency of the book is to deprave and corrupt morals, of course you will acquit; on the other hand, if you’re satisfied that the book does have the tendency to deprave or corrupt, of course you would not hesitate to say so…you are the judges of the matter.”

When the jury in The Chatterley Affair retires for deliberation, the scene becomes more like its counterpart in 12 Angry Men. The foreman takes over by generating a conversation and expression of opinions on the central question not as an abstract dealing, but as a personal question which everyone must be capable of answering after reading the book. As members of society called upon to ban a book for its tendency to deprave and corrupt, the question must start with them. The foreman poses the question as such: “do any of us think that we’ve been depraved or corrupted by reading Lady Chatterley’s Lover….we have been picked at random, 12 ordinary men and women…if the book has a tendency to deprave and corrupt, then it’s likely, isn’t it, that it would have had that effect on us, or at least some of us, so has it?” Like the jury in the 12 Angry Men, some came in with preconceived notions that jury duty is just another day off work. Helena asked Keith on the very first day of jury duty: “So what’s the job you’re not doing today?”

However, once they realize the duty of having to tell people what to read or not, they begin to offer objective opinions based on their subjective experiences as members of society. The underlying reasoning being that ‘I wouldn’t want people telling me what to read so why should I tell other people what to read?’ The foundational reasoning in the 12 Angry Men can be stated as, ‘if 12 people shall determine whether I live or die, I shall want such determination by deliberation not by simple majority ballot cast in haste.’

The Verdict is not like the other two films. In fact, it is one of the traditional films in which the focus is not on the jury; it is on the lawyers and the jury is seen but not heard. The film is a 1982 courtroom drama that focuses on Paul Newman, a clumsy alcoholic ambulance-chasing lawyer who takes on a medical malpractice case in order to improve his own degenerate condition. However, his self-interest is quickly overshadowed by his wish to do what is right for his client who is in a vegetative state.

What is relevant about The Verdict is not the kind of deliberations in both 12 Angry Men and The Chatterley Affair; it is what the jury is told in summation. After an uphill battle with a powerful opposing law firm and an influential Catholic institution, Newman resorts to playing on what ordinary people feel about justice and the law. His assumption is that most people are regularly angered by the failure of law and justice. However, individuals often remove themselves from the functioning of law and the deliverance of justice. Not many people think of jury duty as a way they can improve the system of justice. Therefore, Newman’s closing arguments portrays the jury as those with the true ability to reclaim justice and redeem the justice system, which he paints as tainted with the trappings of power and wealth.

Even though the jury has nothing to say, Newman unveils the greatness of their role in the application of law, especially at a time when society is questioning the ability of the courts to render justice. He calls on the jury to reclaim their role and rescue the system. In a very hopeless and reluctant spirit, Newman renders a call to jury duty by making a compelling statement about justice as something that can be bought, hence only the rich can have it. He states, “ you know, so much of the time we are just lost, we say please God tell us what is right, tell us what is true…when there is no justice the rich wins the poor are powerless. We become tired of hearing people lie, and after a time we become dead…a little dead we think of ourselves as victims, and we become victims…we become weak. We doubt ourselves, we doubt our beliefs, we doubt our institutions, and we doubt the law.” This statement mirrors the frustration of ordinary people against their institutions of justice, but instead of thinking of themselves as powerless victims, Newman challenges them to use their jury power to remedy the institution of justice.

Like in The Chatterley Affair, Newman discredits the letter of the law, symbols of justice, and the officers of the court, and endows the jury with higher moral authority. The jury is deemed not only as transcendent judges of facts, but as the law itself. Newman continues, “[b]ut today, you are the law. You are the law! Not some book, not the lawyers, not the marble statue or the trappings of the court. See, those are just symbols of our desire to be just! They are in fact a prayer! They are a fervent and a frightened prayer. In my religion, they say act as if ye had faith, faith will be given to you. If we aught to have faith in justice, we need only to believe in ourselves and act with justice! See, I believe there is justice in our hearts.” The jury suddenly becomes demigods with the providence to translate society’s desires and prayers for justice into reality. This is a message to every ordinary man or woman of society; that we can rescue the law and the institution of justice if we do our jury duty and uphold the laws.

However, while these films establish a glamorous picture of jury duty, most courtroom films ignore the fundamental influence of the jury on the outcome of cases. According to Jeffrey Abramson, “[w]hether from respect for the sanctity of juries, the awe of their oracular mystery, or just plain fear of what lay inside Pandora’s box, the law regards the jury room as virtually off limits to journalists and outside observers.” Perhaps it is a conscious decision to preserve their independence, neutrality, and impartiality, by taking their deliberations away from the public light. But this invisibility and absence of a representative to respond to public accusations of naïveté and unfairness are producing some repercussions on the jury system. Nancy Marder states that the “American jury is an institution that has proven resilient in the past and yet remains vulnerable in the future.” One aspect of the jury system under threat is the gradual abandonment of unanimity of decision that usually compels further deliberation rather than quick votes.

The press and a few state legislators constantly depict the jury system as in need of immediate reforms, when in fact, there is very little wrong with the system. The temporal and case-by-case nature of every jury makes the system unpredictable and progressive. No one can predict what the next jury will do at any given trial. It might even be that “press and legislative focus on perceived weaknesses of the jury may deflect attention from weaknesses of other institutions.” Of all immediately needed reforms to the justice system, the jury system is not one of them. The system remains functional and faces no major threats, other than a disinterested public. However, we must guard against the elimination of opportunities for deliberation and not reduce jury duty to the art of listening and casting votes. The jury must feel like they have a major stake in the case beyond that of the parties, because both the winner and the loser return to and live in society.

The jury system remains part of our judicial system as one of the major judicial checks and balances in the total functioning of a nation under law, but the only times most people think about the role of the jury in the administration of justice is when the media blames them for something wrong with the outcome of a particular case, or when the individual receives that inevitable summons to jury duty. For many, only when the voucher of possible excuses have run dry do they show up for voir dire hoping not to survive a strike for cause or a peremptory strike, excepting situations in which the juror becomes personally interested in the case and can’t wait to be in court.

Without the jury, the justice system will constantly be under major public scrutiny for credibility. The jury is a mitigating element in a system many view as far removed from reality and full of greedy selfish lawyers. As Phoebe Haddon puts it, “the fact of popular participation through the jury makes tolerable certain decisions which the litigants or the public would otherwise find unacceptable, because the jury verdict is seen as the product of the group, and thus the legitimacy of the result is supported in a manner that might not be attainable if one person, the judge, decides.” However, the jury remains on the sideline of popular culture because when seen in movies, they are almost never heard; they are passive rather than active.

In conclusion, perhaps the invisibility of the jury in the media and popular culture is fundamental to maintaining its credibility and value to our adversarial system of justice. Knowing how each jury came to conclusion on their decision and verdict might expose them to further public scrutiny and doubt, which offers a compelling argument that they must in good faith be left out of popular culture and public light. However, the jury already takes enormous criticisms for some verdicts, and therefore needs the public to understand the processes behind their decision-making.

Moreover, the mystery surrounding their civic responsibility in reality and popular culture makes jury duty one of the most abhorred civic responsibilities around. It is hard to willingly participate in an institution when all one knows is that one’s decision is a matter of life or death, damages or nothing, for someone else. Hence, maybe we should slide the curtain a little in more films and let the public into the jury deliberation room so that ordinary people can understand the process of decision-making by the jury and how fundamental their role is to our justice system.

The Author

Joseph Kaifala is the founder of the Jeneba Project Inc. and co-founder of the Sierra Leone Memory Project. He was born in Sierra Leone and spent his early childhood in Liberia and Guinea. He later moved to Norway where he studied for the International Baccalaureate (IB) at the Red Cross Nordic United World College before enrolling at Skidmore College in upstate New York. Joseph was an International Affairs & French Major, with a minor in Law & Society.

He holds a Master’s degree in International Relations from the Maxwell School at Syracuse University, a Diploma in Intercultural Encounters from the Helsinki Summer School, and a Certificate in Professional French administered by the French Chamber of Commerce.

Joseph was an Applied Human Rights Fellow at Vermont Law School, where he completed his JD and Certificate in International & Comparative Law. He is a recipient of the Vermont Law School (SBA) Student Pro Bono Award, Skidmore College Palamountain Prose Award, and Skidmore College Thoroughbred Award.

Joseph was a 2013 American Society of International Law Helton fellow. He served as Justice of the Arthur Chapter (Vermont Law School) of Phi Alpha Delta Law Fraternity International. He is a member of the Washington DC Bar.

Article picture: Theatrical poster for the release of the 1957 film 12 Angry Men, an adaptation of the courtroom drama of the same name. Source: Wikipedia.