Cyber Warfare in International Law

By Ziyad Hayatli

Published on December 6, 2018

On Sunday the 14th of October, Dutch defence minister Ank Bijleveld declared that the Kingdom of the Netherlands is in a “cyberwar” with Russia after it was alleged that a team of Russian agents were caught trying to mount a “cyber attack” on the Organisation of the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, in the Hague. Russia has described these allegations as a “rich fantasy” and that it was the victim of “yet another stage managed propaganda campaign.”

In this particular case, images were released detailing the identities of the alleged Russian GRU agents, as well as the supposed electronic equipment they were carrying around with them which presumably they had hoped would assist in gaining access to the networks of the OPCW.

The motivation of this (as reported in the mass media) was related to the poisoning of a Russian spy, Sergei Skripal, in Salisbury UK, and the alleged chemical weapons attacks carried out by the Russian backed Syrian Arab Army in Douma, Syria. The OPCW is investigating both alleged events.

Most relevant to this article, however, is a joint statement made by British Prime Minister Theresa May and her Dutch counterpart Mark Rutte, which stated that the alleged plot against the OPCW demonstrated the “GRU’s disregard for global values and rules that keep us safe.” This raises the question posed by this article – what does international law actually say about cyber attacks?

Jus ad bellum – Going to War

Before we launch into assertions and statements, it is important to identify what a cyber attack actually is. Unlike conventional warfare, which takes place in the physical world and has “real” physical effects recognisable to all, cyber attacks are themselves intangible, and whilst some may have a direct kinetic effect, others have indirect consequences.

Nils Melzer, of the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDR), wrote a research piece on cyber warfare in international law and also used the well-known “Tallinn Manual” on cyber operations, produced by NATO, for guidance.

Firstly, cyber attacks and cyber warfare take place in cyberspace; an electronic space that is created, maintained, and owned by public and private stakeholders. It differs from the traditional theatres of war (land, sea, air and space) in that it is entirely manmade and not subject to traditional physical boundaries like geographical borders. Cyber attacks must also be carried out through cyber means – in other words, the physical destruction of telecommunication networks by bombardment would not constitute a cyber attack.

The Tallinn manual goes on to place cyber attacks under the umbrella term of Computer Network Operations (CNO), under which there are three types of activity:

1. Computer Network Attack (CNA) – Operations aiming to “disrupt, deny, degrade, or destroy information resident in computers and computer networks, or the computers and networks themselves.”

2. Computer Network Exploitation (CNE) – Operations aimed at collecting intelligence and data from adversary automated information systems or networks. This is linked to and has parallels with espionage.

3. Computer Network Defence (CND) – Actions taken to protect, monitor, analyse, detect, and respond to unauthorised activity within information systems and computer networks. And prevention of CNA and CNE through intelligence, counter intelligence, law enforcement, and military capabilities.

What is apparent where warfare is concerned, is that this terminology is specific to operations conducted in cyber space, and is distinct from the existing concepts of warfare in international law, which uses terms such as “force” (implying a physical element) and “armed attack” (implying the use of a weapon).

For example, Article 2(4) of the UN Charter, which prohibits the use or threat of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of a state, is one of the cornerstones of jus ad bellum, or, in other words, the legal restriction of going to war. The drafters of the UN Charter had the foresight to add a clause at the end, qualifying the prohibition to the threat or use of force to “or any other manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations.” This “soft” language (i.e. malleable or open to interpretation) leaves a wide scope of debate as to whether it covers cyber warfare or not. Guidance can be taken from the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, specifically Articles 31 and 32, which encourage interpreting such articles in good faith and state that the preparatory works of a given treaty or charter (known as Travaux préparatoires) can be examined to work out the object and purpose of a treaty. In the case of the UN Charter, these Travaux préparatoires include the documentation of the UN Conference on International Organisation, which shows that the prohibition on the use of force was only intended to include actions that cause direct injury, death, or destruction; other suggestions, for example by the Brazilian state, to include the threat of economic sanctions, was rejected during the conference in San Francisco.

Hypothetically speaking, certain cyber attacks, such as the halting of automated manufacturing systems, or the “blinding” of another state’s radar and air defences, do not include direct destruction, injury, or death. On the other hand, they can be seen as highly provocative and threatening, and therefore contrary to the UN Charter’s purposes of maintaining international peace and security. Whether they constitute an “armed attack” and whether states are therefore able to use force in response to such provocations is a separate matter.

This brings us onto Article 51 of the UN Charter, which provides the right of states to use force in self-defence if subjected to what amounts to an armed attack. The use of the word “armed” in this case implies the use of some form of weapon. Let us consider, hypothetically, a piece of software designed to shut down the military radar systems of a state. Would this programme count as a “weapon”? If not, then it would not be an armed attack. It may be provocative and contrary to the object and purposes of the UN Charter. It may even be a “wrongful act”, but it does not fulfil the criteria for replying with force in self-defence.

It can be argued that such software programmes can be considered weapons. In the International Court of Justice’s advisory opinion on prohibition of nuclear weapons ([1996] ICJ Rep 226) the court clarified that Articles 2(4) and 51 of the UN Charter do not refer to specific weapons, but any weapon (see paragraph 39). If we were to take guidance from the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (UN 1155 UNTS 331)and define the term “weapon” in “good faith”, then it can be expanded to almost anything used by a state in a malicious attack against another.

There is a further complication to consider. In conventional warfare, attributing an action to a state is relatively straightforward. Proving that a state is responsible for an armed attack depends upon forensic and physical evidence that its armed forces, agents, or even those by proxy, has carried out a physical and material attack. With cyber warfare, or cyber operations, it is much easier to mask the source of an attack through what is known as “IP spoofing” (forging the address of the source of an attack) and the use of “botnets” (an interconnected network of computers that have been compromised with malicious software which allow them to be controlled). Even when the effects of the hacking are physical, it is difficult to prove the responsible party.

What becomes evident as one looks into this subject is that the language used can be considered outdated. The principles of jus ad bellum and prohibition on the use of force were set out in 1945, but the world has changed since then. Mils Melzer for the UNIDR concludes that:

“Overall, however, there still is no consensus as to the precise threshold at which cyber operations should amount to an internationally wrongful threat or use of force. In fact, there is not even an identifiable controversy with clear positions and conflicting criteria. The truth is that cyber operations, almost always falling within the grey zone between traditional military force and other forms of coercion, simply were not anticipated by the drafters of the UN Charter and, so far, neither state practice nor international jurisprudence provide clear criteria regarding the threshold at which cyber operations not causing death, injury or destruction must be regarded as prohibited under article 2(4) of the UN Charter.” – page 9 of his report on cyber warfare and international law for the United Nations Institute on Disarmament Research. Jus in bello – Conduct within Warfare

Whether a cyber operation amounts to an armed attack, and whether the aggrieved state may use such an incident as a legal casus belli (legal justification to commence conflict) is one question. The other is conduct within warfare, or once a war commences.

Cordula Droege writes in the International Review of the Red Cross(Volume 94 No 886 Summer 2012) about how the biggest concern over cyber warfare is the interconnectivity between the internet and civilian infrastructure. Most military networks rely on civilian infrastructure, such as undersea fibre optic cables. Civilian vehicles, such as shipping and passenger aircraft, rely on Global Position System (GPS) satellites which the military also uses. This means that it is increasingly difficult to differentiate one from the other. Even if the requisite differentiation is made, their interconnectivity means it is difficult to attack a military network without the risk of affecting the civilian population, and in turn the risk of endangering civilian lives. This means that the rule of distinction, a staple of international humanitarian law whereby a military must distinguish between civilians and legitimate targets, is not so easily applied in this case, even when care is supposedly taken.

One example of such an occurrence is the Stuxnet malicious “worm”, a piece of malicious software that targets automation systems known as SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition), usually found within manufacturing and industry. It was uncovered in 2010, when it attacked and destroyed centrifuges belonging to the Iranian Nuclear Programme by causing them to spin and tear themselves apart. The first thing to note is that although it is speculated to have been developed by American and Israeli agents, the source of the attack was never uncovered. Attributing the responsibility squarely on anyone has been nigh impossible. Speculations were based on how the software code was written. Secondly, this is an example of a cyber attack, achieved through “cyber means”, but which nonetheless physically destroyed and damaged equipment. This is a demonstration of how infrastructure, be it power plants, water treatment systems, or even transportation, is somewhat automated and vulnerable to outside attack due to its interconnectivity. Despite this attack being specific in its nature and not affecting civilian lives directly and maliciously, it spread, much like a virus, and infected other systems within Iran, Indonesia, and India among others.

Whether the Stuxnet attack is in accordance with international law firstly depends on whether the perpetrating state or Iran considered themselves in a state of conflict with one another at the time. Only one of those parties is required to hold this belief for the rules of war to apply. If, for sake of argument, Israel was to be held to account, it can justify its action by stating that it is indeed in a state of war with Iran via its proxy, Hezbollah, in Lebanon, with which they have had hostilities. Secondly, it would depend on whether these centrifuges were being used to enrich Uranium purely for a nuclear weapons programme – rendering them a legitimate military target. Iran’s right to self defence in the face of this attack is also dependent upon whether it falls under the definition of an “armed attack” pursuant to Article 51 of the UN Charter. This real world example demonstrates how cyber warfare has a large scope for interpretation and debate.

Unsurprisingly, the way that states are approaching this new front of human existence varies wildly. The NATO produced “Tallinn Manual” is an attempt by an international governmental organisation to understand cyber warfare within the context of international law, and to prepare for it. Their Centres of Excellence, one of which produced this manual, aims at educating, training, and preparing Member States in their respective specialisations.

The United Kingdom has made efforts to introduce basic rules of conduct within Cyberspace during the Global Conference on Cyberspace. Also known as the “London Process,”, this is part of a series of conferences held around the world every two years. The general approach of the UK is that what is unacceptable offline, should by extension be unacceptable online, and not to “stifle” it any further or place too many restrictions. The UN Institute for Disarmament Research has suggested that this ongoing dialogue could be used as a “confidence building” measure between states, corporations, and non-governmental organisations and establishing “norms” of behaviour and transparency, as opposed to simply writing up an international treaty with more “hard” language (UNIDIR, Ben Baseley-Walker 2011). This is with the understanding that international law is shaped and created through state practice and opinio juris>. Where enforcement is a challenge, the risk of isolation, – be it diplomatic or economic, – becomes the other de facto method of enforcement in which the international society of states partake.

Conversely, the Russian Federation has been attempting to draw up a treaty of sorts to regulate cyberspace since 1998 through the General Assembly. In 2008, the Federation contributed to drawing up such a multilateral treaty within the Shanghai Cooperation Organisaton, which includes China, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, and India. This is a more direct and “top-down” approach, and whether it will work better than a “confidence building” measure is dependeant upon the more practical realities of cyber warfare. For example, if a treaty is drawn up between a group of states about the production of nuclear weapons, then monitoring the adherence to the treaty should be relatively simple. Though, the recent debacle between the United States and Iran would make one sceptic about just how useful treaties are in these matters. With cyber warfare, there are no Uranium enrichment facilities or satellite images of missile sites to point to. The problem of attributing cyber attacks to states, and the ease with which a party can disguise such an attack, means the international enforcement of such a treaty would prove problematic. From a cynical point of view, there is also the fear that such treaties may be used to justify tighter controls on a tool that allows people to communicate, document, and learn from one another.

Information War – Concluding Remarks

Cyberspace and the internet has become synonymous with the notion of “information sharing.” Before that, inventions such as the radio and the telegram were key to controlling the flow of information, and through that influencing public opinion. Governments have always used information technologies to achieve this purpose.

One of the key examples, which may be considered a “cyber operation” before its time, is known as the Zimmerman Telegram in the First World War. It was a communication sent by Germany to Mexico in 1917, proposing an alliance and encouraging Mexico to attack the United States to regain territory lost in 1836. British intelligence intercepted this private communication and made it public, helping to generate popular support within the United States for entering the First World War and arguably changing the odds to be infavour of the Allied Powers against the Central Powers. This particular example, if the official narrative is to be believed, shows the intelligence service of a nation seizing a rare opportunity to turn the tide.

More recently, in 2010, it was uncovered that the US Department for International Aid, USAID, developed a social network to be used in Cuba by ordinary Cubans. This was an exciting proposal in a country where internet access is tightly controlled and limited under the existing regime. The network was to be called Zunzuneo, and was designed to allow Cubans to communicate and share information cheaply. What is ominous, however, is how this network was advertised as a private enterprise and collected masses of data on users in order to gauge their political leanings. The reason? Sending out mass text messages, chosen at an opportune time, to trigger a revolution and eventually a regime change. An agent was even reportedly sent to install internet connection equipment not usually available to the public. Cyberspace was effectively created and used in an attempt to undermine a regime. As repressive as the Cuban regime is, when such projects come to light, they more often than not jeopardise the opposition and allow them to be painted as foreign agents with more ease.

The importance of influencing public opinion to, in turn, influence a hostile or allied state to one’s advantage has always been recognised, no matter the political system. The USA itself is now investigating social media influence during its most recent presidential elections, and the ever looming allegation that Russia was involved. It has become clear that the “information war” is a new reality built on the most pervasive manifestation of cyberspace in our everyday lives; the internet. Certain governments are therefore beginning to view the internet as an “achilles heel” to their social fabric, and their answer has been to impose tighter controls. China, which leads the world on cyber surveillance, has been exporting its analytical and surveillance tools to authoritarian governments and training their officials for some time. In a disturbing report by Freedom House, it is claimed that on a global scale, internet freedoms are actually on the decline.

As with any relatively new development, the global society seems to be grappling with how best to deal with cyberspace. What the individual sees as a tool that allows them to view and share content, a nation state sees at best as a weapon, or at worst, a thing to fear. The original principles around non-aggression and mutual respect of sovereignty are being challenged due to their outdated language and concepts. What this means for international law is that states now have the responsibility to shape what the future of cyberspace will look like: firstly through state practice and opinio juris, which forms the basis of customary law; secondly through any treaties they decide to draft. The coming decades will be critical as our dependency on the internet, both as individuals and governments, increases.

The Author

Ziyad holds a BA in journalism and philosophy, as well as a masters LLM in international law.

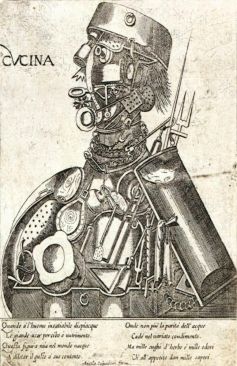

Article picture: Unknown engraver – Humani Victus Instrumenta – Ars Coquinaria. Source: Wikipedia