Codification of Welsh Law Association of London Welsh Lawyers 8 March 2018

By Lord Lloyd-Jones

Published on March 16, 2018

I have been asked to say something about the context in which issue of the codification arises. I will identify the problem and Nicholas Paines QC and the Counsel General will then tell you how they propose to solve it.

This is a very exciting time for the law in Wales. Since the acquisition by the National Assembly of primary law making powers under Part 4 of GOWA 2006, the extensive use made by the National Assembly of these powers means that for the first time since the age of the Tudors it has once again become meaningful to speak of Welsh law as a living system of law. As a result of this, and as a result of the corresponding development of Westminster legislating for England only, we are now witnessing a rapidly growing divergence between English law and Welsh law. At present this is particularly apparent in areas such as education, planning, social services and residential tenancies. No doubt, this divergence will accelerate and extend more broadly when the Wales Act 2017 – our fourth devolution settlement but the first on a reserved powers basis – comes into force shortly.

The Law Commission is the Law Commission of England and Wales. From the start of devolution it has worked closely with the Welsh Government and the National Assembly. In the most recent phase of devolution in Wales, the Assembly has used its primary legislative powers to implement Law Commission recommendations. The Social Services and Wellbeing (Wales) Act 2014 implements Law Commission proposals on Adult Social Care. The Renting Homes (Wales) Act 2016 implements the Law Commission’s 2006 report on Renting Homes, updated in 2013 in a report with specific reference to Wales. It is significant that this report has been implemented in Wales but not in England – affording to Wales a far superior system concerning residential tenancies.

There were, nevertheless, deficiencies in the machinery of law reform in relation to Wales. It had simply failed to keep pace with devolution. However, these deficiencies have now, I believe, been rectified by legislation in Westminster. The Wales Act 2014 amended the Law Commission’s statute, the Law Commissions Act 1965, with the result that the Welsh Government can now refer a law reform project directly to the Law Commission. Moreover, the Welsh Ministers are now under a statutory duty to report annually to the Assembly on progress (or lack of progress) in the implementation of Law Commission proposals in the devolved areas.

In a separate development, in 2013 the Law Commission set up a Welsh Advisory Committee, entirely outside the statutory scheme. This has become an important voice for Wales on the subject of law reform.

The problem of accessibility

At an early meeting, the members of the Welsh Advisory Committee impressed upon the Commissioners the sheer complexity and inaccessibility of the law applicable in Wales.

Problems of accessibility arise at different levels. First, one has to be able to find the applicable rule or rules. That in itself can be a considerable challenge. It can often require a great deal of skill and perseverance in order to discover what precisely is the law in a particular devolved area. Then, once it has been found, one has to be able to understand it. At a time when access to lawyers has itself become something of a luxury – with legal advice being expensive and with reductions in the levels of legal aid available – it becomes even more important that the law, once found, is intelligible. And we all know that – at least so far as Westminster legislation is concerned – it is often so complex that it is barely intelligible to trained lawyers, let alone to laymen and women.

As a result in 2013 the Commission undertook a project on the Form and Accessibility of the Law applicable in Wales. This was undertaken at the request of the Welsh Government and, following an intensive consultation exercise, it reported in 2016. As we started on the project, we were made aware of the scale of the problem and the extreme difficulties which are being faced by legal professionals and others who need to know what the law is. For example, we were told by the judges in Wales of the difficulties which they are encountering and, in particular, of the problems presented by lawyers appearing before them who are either unaware that the law of Wales is different in a particular area from the law of England or who are not familiar with its content. We were told that this was particularly so in the area of law concerned with social services.

The complexity and inaccessibility of the law are now a huge problem. One cause of this unsatisfactory situation seems to be the way in which devolution has developed. For example, the fact that powers to make subordinate legislation have been transferred under successive devolution settlements makes it unclear which body has the power to make law or to exercise legal powers.

A second cause of the impenetrability of legislation applicable to Wales is that primary legislation in the devolved areas may now be amended by both the Westminster Parliament and the National Assembly. This is a further source of confusion. This is demonstrated by an example, for which I am indebted to Keith Bush QC. Section 569 of the Education Act 1996 currently has nine sub-sections. On careful consideration it will be seen that, within a single section:

(a) subsections (1), (4), (5) and (6) apply in relation to both England and Wales (although the effect of subsection (6) in relation to Wales is unclear); (b) subsections (2) and (2A) now apply only in relation to England; and (c) subsections (2B) and (2C) apply only in relation to Wales.

Again, there are increasing numbers of provision of this kind, which require the reader to be able to identify, even within a single section, different provisions which apply to different countries.

A third source of difficulty in this regard – but one which is not connected with the consequences of devolution or indeed limited to Welsh law – is that the traditional style of amendment employed in Westminster is just to publish the amendment – not the amended text. Take, for example, section 25 of the Wales Act 2014 – the provision which permits the Welsh Government to refer a law reform project to the Commission:

“25. The work of the Law Commission so far as relating to Wales (1) The Law Commissions Act 1965 is amended as follows.

(2) In section 3(1) (functions of the Commissions), after paragraph (e) insert—

“(ea) in the case of the Law Commission, to provide advice and information to the Welsh Ministers;…”

On its face, the statutory provision is meaningless. Unless you relate it back to the statute that is being amended you can have no idea of what it means. This is a relatively simple instance, but in many instances a statutory provision is amended time and time and time again, resulting in an impenetrable mess.

A fourth cause of the difficulty – and perhaps the main cause – is the sheer volume of legislation and the fact that different rules applicable to a given situation are not to be found collected together but are scattered all over the statute book and have to be hunted down. The Law Commission in its 2016 report on the accessibility of the law applicable in Wales gave the following example. It has been much cited since it was published. Depending on how widely “the law of education” is defined, the law which applies to education in Wales is to be found in between 17 and 40 Acts of Parliament, 7 Assembly Measures and 6 Assembly Acts, as well as hundreds of statutory instruments.

Unless something is done, this problem of the inaccessibility of legislation applicable in Wales will grow much worse.

If Wales is to succeed in the changed circumstances of devolution, the law of Wales must be made readily accessible to its subjects – in particular to those in many different walks of life who have to apply it. This is so for two fundamental reasons.

First, it is essential to the rule of law in any nation that the content of the law should be readily accessible. Accessibility of our law is not an optional extra, something that is nice to have. The European Court of Human Rights in the Sunday Times case in 1979 said this:

“[T]he law must be adequately accessible: the citizen must be able to have an indication that is adequate in the circumstances of the legal rules applicable to a given case. … [A] norm cannot be regarded as a “law” unless it is formulated with sufficient precision to enable the citizen to regulate his conduct: he must be able – if need be with appropriate advice – to foresee, to a degree that is reasonable in the circumstances, the consequences which a given action may entail.” Similarly, Lord Bingham in his great work on the Rule of Law identified as a primary consideration that the law must be “accessible, and, so far as possible, intelligible, clear and predictable”. If citizens are not able to find out what the law is, they are no better placed to plan their futures than if they were subject to the arbitrary exercise of governmental power.

Secondly, accessible laws are crucial for commercial certainty and, therefore, for the future economic prosperity of Wales. No one would choose to do business in a nation where the parties’ rights and obligations are vague or undecided. Put bluntly, “Who is going to invest in a nation where you can’t know with any degree of certainty what its laws are?”

It seems to me, therefore, that perhaps the greatest single challenge we now face is to make the law of Wales accessible to the people of Wales. The volume and complexity of the legislation produced so far by the National Assembly and the Welsh Government, when considered in conjunction with legislation applicable to Wales made in Westminster or Whitehall, suggest that this will be no easy undertaking.

In a moment, Nicholas Paines will tell you about the Law Commission recommendations in respect of Wales. First, let me say something very briefly about consolidation and codification of statute law in more general terms.

Consolidation

Consolidation aims to make statute law more accessible and comprehensible by drawing together different enactments on the same subject matter to form a rational structure and making the cumulative effect of different layers of amendment more intelligible. In all purely consolidation exercises, the intention is that the effect of the current law should be preserved. However, there is usually scope for modernising language and removing the minor inconsistencies or ambiguities that can result both from successive Acts on the same subject and more general changes in the law.

Modern methods of updating legislation – most significantly the Internet – have reduced the pressure to consolidate simply to take account of amendments, provided, of course, that they public have access to such up to date resources. There is still, however, a need for consolidation as a process. This is usually because the law on a subject is found in a number of different Acts or instruments, or because layers of amending legislation have distorted the structure of the original Act. A good consolidation does much more than produce an updated text. And the need to consolidate may be particularly acute after repeated legislative activity in a particular area of law over a period of several years, without the original legislation having been replaced. The language can become out of date and the content obsolete or out of step with developments in the general law.

The consolidation of statute law has been an important function of the Law Commission since its creation. The Commission has been responsible for 222 enacted consolidation Bills since it was established in 1965. Its most recent consolidation exercise resulted in the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014. Some of the larger consolidations can each take two or three years to complete. Usually, there is little point in starting a consolidation unless the underlying law is likely to remain stable for the period the project will take.

To produce a consolidated Welsh statute book would be an undertaking of massive proportions which, in my view, would be likely to take a generation to accomplish. It would require huge resources both in financial terms and in terms of the required number of skilled legislative counsel. It would also require to be a high priority within the Welsh Government and would require legislative time within the National Assembly. At the moment it is entirely understandable that, the Assembly having only comparatively recently acquired direct primary legislative powers, successive Welsh Governments will want to concentrate on fashioning new laws for Wales and achieving practical reforms in the devolved areas. Consolidation of the back catalogue of laws is, understandably, not a high priority.

The Welsh Government and the Assembly have, in fact, made a start by ensuring that when the Assembly legislates it states the law as amended in a readily comprehensible and complete form. Moreover, they pursue a policy of restating the law separately for Wales, as opposed to merely making amendments to a UK Act in its application to Wales. This is a useful start but it has its limitations. It is necessarily restricted to those policy areas within which legislation is passed. This means that the enactment of a Welsh statute book cannot be undertaken systematically and makes complete coverage a distant possibility. Consolidation is a long term solution, but if it is set in train now it could gradually improve the quality of the statute book.

Codification

There is, however, a much more radical possible approach to the future form of Welsh legislation. This would involve the Assembly in producing US style codes, each dealing with a distinct subject matter. A system of codes would mean that all of the statute law on a particular subject could be found in one place where it would appear in a properly organised form, set out systematically in chapters. Thereafter, any amendment would be by amendment of the code which would remain an up to date statement of the legislation applicable to the particular field.

This is an approach which has been advocated for some time by the former Lord Chief Justice, Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd. His point is that Wales is free from the fetters of tradition so far as the drafting of legislation is concerned and that, if Wales thinks sufficiently boldly and innovatively, legislation drafted in Cardiff can improve on that produced in Westminster.

This certainly struck a chord with the Law Commission which is currently close to completing a project which involves – although it is not limited to – the codification of the law on sentencing procedure. It hopes to replace a mass of different statutory provisions with a single code which will be the only required point of reference for practitioners and judges. It is easy to think of subjects in the devolved areas which might benefit from a similar treatment; education and planning law spring to mind.

I am sorry if this sounds like a counsel of despair. It is not meant to be. On the contrary, at this early stage in the history of devolution in Wales the position remains remediable. While, comprehensive codes covering the entirety of the devolved areas would be a massive undertaking, prompt action focused on specific areas could confer real benefits within a relatively short term. But it seems to me that this needs to be set in motion soon while the position is still remediable.

The Author

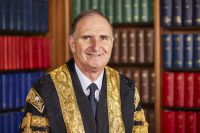

Justice of The Supreme Court, The Right Hon Lord Lloyd-Jones

David Lloyd Jones, Lord Lloyd-Jones became a Justice of The Supreme Court in October 2017.

Lord Lloyd-Jones was born and brought up in Pontypridd, Glamorgan where his father was a schoolteacher. He attended Pontypridd Boys’ Grammar School and Downing College, Cambridge. He was a Fellow of Downing College from 1975 to 1991. At the Bar his practice included international law, EU law and public law. He was amicus curiae (independent advisor to the court) in the Pinochet litigation before the House of Lords.

A Welsh speaker, Lord Lloyd-Jones was appointed to the High Court in 2005. From 2008 to 2011 he served as a Presiding Judge on the Wales Circuit and Chair of the Lord Chancellor’s Standing Committee on the Welsh Language. In 2012 he was appointed a Lord Justice of Appeal and from 2012 to 2015 he was Chairman of the Law Commission.

Lord Lloyd-Jones is the first Justice of The Supreme Court to come from Wales Image credit: © UK Supreme Court / Kevin Leighton

Article picture: Welsh flag. Source: Wikipedia