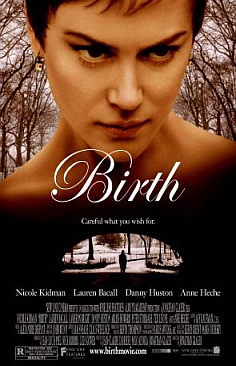

“Birth”-Jonathan Glazer (2004)

By Chris Middlehurst

Published on February 13, 2017

I have an immense fondness for the films of Jonathan Glazer, not least because he is one of the very few filmmakers on this planet whose output I can actually keep up with. There are greats by the likes of Hitchcock, Carpenter, Wilder and many others that I have not managed to see yet, even when some of these filmmakers have been dead for a long time now.

Jonathan Glazer has made only three films in 17 years, each of them under two hours long: the man has been compared to Kubrick not merely for his obsessive attention to detail and technical brilliance, but also for the lengthy time spent in between projects. In this respect, Glazer is not a filmmaking factory like Ingmar Bergman or Adam Sandler. Rather, he is an extreme artisan, a maverick who will hand in his essay two years after the professors themselves have died and thus score himself a double first, a footballer who scores the goals while the rest of the team have turned to punditry or shop adverts. You would not be wise to hold your breath for the next Jonathan Glazer project, but you might just wish that you secretly had. Unlike Kubrick, however, whose later films were impressive and overlong in equal measure, Glazer is not patient to the point of being frustrating. Indeed, I feel that he must be congratulated for the relative brevity of his films, in comparison with some of the blockbuster atrocities of today which are twice as long but contain less than half as many good ideas.

Beginning his film career with Sexy Beast in 2000, Glazer threw himself into the brilliant script by sadly separated writing team Louis Mellis and David Scinto to turn in one of the best British gangster films ever made. Ben Kingsley tore his reputation apart as a charmer and sank his gnashes into creating one of the most memorable psychopaths in England (and that’s saying something, for there are indeed a few) whilst Ray Winstone showed that he could still be intimidated by somebody. Meanwhile, Ian McShane showed that he could indeed slick his hair back just like the best of them and James Fox showed that he could, well…play James Fox. In Under the Skin, Glazer enabled Scarlet Johannson to display her true colours as a beautiful but menacing extra-terrestrial: that film even used real life members of the public who didn’t even know they were being filmed. God only knows what their reactions must have been when they found out. Both Sexy Beast and Under the Skin were completely different projects in outward appearance, but they did share a few things in common: outsiders, a surprising plot structure and sheer cinematic wizardry.

Which brings me to give Birth to a review of his middle project, his in the wilderness enterprise, a sort of cinematic Gap Yah if you like. I must say that there is a wildly uneven tone to this film, which veers between mawkish department-store-style Christmas season sentimentality and full-blown ominous bladder throttling horror: either which way, both made me hold my seat until my knuckles threatened to pierce through my skin. The film starts oddly: a wonderfully framed shot of a man dying underneath a bridge as it expands to resemble a foetus in the womb is then followed by a bit of a lazy slow-mo shot of a baby being held after a water birth. I myself might have used more subtle imagery, such as a butterfly emerging from a cocoon or a swab of mayonnaise being squeezed out of a tub, but there you go, I’m not Jonathan Glazer. The film then shifts to an engagement party in a posh New York apartment, with the radiant Nicole Kidman and the (ahem!) not so radiant Danny Huston as the man to greet her at the altar. Huston is so strangely gauche in his own way that one can imagine him stepping forward in full groom garb three hours late and shaking Kidman’s hand, saying: “Hey! I’m Danny Huston, nice to meet you. Gee whiz, this wedding is going on a bit! Where’s the groom?”

To cut a short story long, a strange little boy arrives claiming to be Kidman’s ex-husband reincarnated, back from the dead, not as a horse or a goldfish but as a little boy. Boy oh boy, Kidman cries. Yes, I am a boy: I’m also your dead husband, he replies in words to that effect. The drama ensues from there, as Kidman becomes more and more attracted to the idea of her husband returning in another form and Danny Huston becomes more frustrated as he senses not so much the boy as a rival, but rather Kidman’s idea of what the boy represents to her. This is the most interesting aspect of the boy: how frustrating it must feel to be thought of as somebody else by your supposed elders and superiors, especially when the idea that they could be mistaken becomes absurd or even threatening to them. It is Kidman’s brilliant presentation of her character and Glazer’s orchestration of events that turns the film into a masterpiece. It is helped with a strong script co-written by Glazer with Milo Addica and Jean-Claude Carriere, who wrote scripts for the great absurdist Luis Bunuel films.

Glazer displays a love of cinema in all of his films, and Birth is no exception: I listed visual references to Rosemary’s Baby, Les 400 Coups, and Bunuel of course. Even Kidman’s apartment number in the film is 2001, would you believe! Coincidence? I think not. The editing and shot composition is sublime in this film: in one conversation between two characters, Glazer’s changing of lighting during the scene perfectly captures the mood of the characters in a way that elevates the mundanity of the shot-reverse shot combination that we have come to expect from Hollywood into the art that it once was. These are not continuity errors that would fit in a Benny Hill sketch, but rather subtle ways of conveying the characters’ emotions through different measures. Yes, a light switch can indeed make a whole lot of difference to a scene. And I must not end this review without mentioning the wonderful casting direction of Ted Levine and Peter Stormare, better known for playing psychopaths and hitmen rather than regular fatherly blokes. Like the unlikely transformations of Ben Kingsley and Scarlett Johannson, they inhabit their new roles so well that they do not distract from the content of the film. One senses that Glazer has a taste for the unexpected: I hope he will continue to do so in his next project, whenever it appears. Take your time, sir. It can wait. But I wouldn’t hold my breath.

The Author

Chris Middlehurst is The New Jurist film review editor. Chris graduated from Leeds University with a BA in English Literature, where he served as President of the LUU Film Making Society and also took elective modules in Chinese, Italian and World Cinema. He currently lives in Leeds and volunteers regulary at the wonderful Hyde Park Picture House, where he urges film lovers to visit if they get the chance!