Alternative Dispute Resolution

By Charles Parselle

Published on August 19, 2011

Mediation is just one of the forms of dispute resolution that are “alternative” to litigation through the courts. It helps to have some understanding of the others.

The first two forms of dispute resolution fall outside the ambit of any formal procedures.

The first is avoidance, which is a consciously chosen strategy in response to a perceived conflict. This strategy may be called: “Get out of Dodge City.”

There is nothing wrong with getting out of Dodge City, in the face of a stronger opponent, a prize not worth fighting for, fear of worse, or any other number of motivations.

People routinely, and often sensibly, respond to provocation by just ignoring it.

At the other end of the scale of extra-judicial processes, is self-help.

Self-help is an action taken by a person designed to affect a resolution of a problem. Self-help includes murder, though not all forms of self-help are illegal.

Murder is an effective means of resolving conflict by disposing of the opponent, but it suffers from drawbacks: (1) For most people, there is a moral objections: murder is against one of the Ten Commandments – “Thy shalt not kill.” (2) Murder is illegal, and the consequences of getting caught can ruin more than one’s whole day. (3) Even where there is no organized legal system, there is a debilitating consequence to murder: it often results in a blood feud. Such blood feuds may last from generation to generation, and infect an entire society.

Other forms of less drastic self-help may include protesting, striking, theft, and so on. Both avoidance and self-help share in common that they are unilateral and unorganized. All other forms are more or less organized, and are bilateral or multi-lateral.

Straddling the border between organized and unorganized systems is negotiation. Negotiation is by far the commonest method used in all societies for resolving disputes. Most negotiations take place outside of any formal procedure.

Indeed, people engage in negotiations constantly, on a daily basis, as they navigate their way through the day. When a conflict becomes serious enough to involve other people, it moves from the unorganized into the organized area of dispute resolution, and many people retain attorneys or other negotiators to do their negotiating on their behalf.

If negotiations prove unfruitful in terms of affecting resolution, then the parties may simply walk away from the deal. Or, if they cannot, they may resort to arbitration, which is an acknowledged form of alternative dispute resolution, and is very often given legal sanction, meaning that arbitration awards can be enforced in a court of law.

In arbitration, the parties have made the decision that they wish to avoid two features of a court trial. The first is the great expense of litigation; the second is the public nature of litigation.

Arbitration is private, and the decision reached by an arbitrator is between the parties to that arbitration only. Generally speaking, arbitration is much cheaper than a fully litigated case. Parties to arbitration also have the luxury of choosing an arbitrator of their own choice, rather than accept whichever judge the court system provides them.

Also, in a litigated case, all parties must conform to the schedule laid down by the court, and the court’s system consults the convenience of judges more than the convenience of the parties, whereas in an arbitration, the parties can adjust the schedule with the arbitrator according to their own needs and preferences.

However, arbitration shares with the court system one critical feature.

The parties to arbitration are not free to craft their own solution to the problem. Instead, they have already agreed that the decision of the arbitrator will be binding upon all parties. In this sense, arbitration is exactly the same as a trial by judge or jury, which also contains the feature that the parties are bound by the decision, and that decision will generally result in a winner and a loser.

Arbitration may be part of the procedure of a litigated case. For example, in California, in an effort initiated by the courts to reduce the size of their own dockets, a case may be ordered into arbitration, to be heard by an arbitrator on the court’s list of volunteer arbitrators, with rules set down by the court for conducting an arbitration.

However, because there is a constitutional right to proceed to trial by judge or jury, the rules provide that if either party is not intent to abide by the decision of the arbitrator in a court-annexed proceeding, then either party may refuse to accept the arbitrator’s findings, and instead proceed to trial by requesting what is called a “trial de novo,” which means a trial “as if the arbitration had never occurred.

Because of the “de novo” feature, arbitrations are widely perceived by litigants as being a waste of time, just one more hurdle to jump on the way to court trial, and for this reason, this court-annexed arbitrations have greatly declined in popularity, given way instead to growth in court-annexed mediations.

The great majority of arbitrations are contractual, coming about by reason of a prior agreement between the parties to permit a third person, the arbitrator, to decide the issue between them.

The courts are supportive of contractual agreements to arbitration, and the courts will generally uphold arbitration awards. A risk that parties take when they choose an arbitrator to make the decision for them is that the decisions of arbitrators are, in nearly all cases, not subject to any appeal.

The arbitrator’s decision is final, even if the arbitrator has “got the facts wrong,” and even if the arbitrator makes a mistake in law.

The grounds upon which an arbitrator’s Award can be challenged are usually very limited, relating to proven corruption, undisclosed conflict of interest, or excess of jurisdiction, on the part of the arbitrator. In this sense, an arbitrator more absolute power than a judge or jury, whose decisions are subject potentially to two levels of appeal.

It does not hurt to be reminded that the court system itself was once an alternative dispute resolution process, which has superseded older forms of dispute resolution, of which may be mentioned trial by battle, trial by ordeal, trial by compurgation, and trial by torture.

Trial by Battle: It used to be thought that in the event of a dispute, the disputants should resolve the issue by battling it out between themselves, and indeed this method still prevails today: Western movies are full of such examples.

In addition to the strategy of avoidance (“Get out of Dodge City”), there is the strategy of confrontation (“Gunfight at OK Corral,” “High Noon”) This procedure became formalized in the early middle ages when it became the custom for a disputant to pick a champion to engage in the battle on his behalf.

It was still the case that the winner of the battle also won the argument, but the individual disputant did not have to risk his own neck in order to achieve this kind of “justice.” Knights in medieval times would engage in tournaments, at which they would start at one end of the run, and proceed at full tilt on horseback towards their opponent, also on horseback and wearing heavy armor.

The lances would strike the galloping bodies, and if each survived that encounter they would gallop to the other end of the run, and turn in order to face the opposite direction and start again. This turning point was called the tourney, and the knight was said to be “at the tourney,” or “a tourney,” from which we derive the modern term “attorney.”

Trial by Ordeal: Trial by ordeal could be called an unfairly weighted system, often used to “try” witches. The unfortunate lady would be weighed down with stones in a sack, and thrown into a pond. If she survived, that was by the grace of God, and she was innocent. If she drowned (nearly always the case) that proved she was guilty.

If she might be made to grasp burning coals; if by God’s mercy her hand did not blister, she was innocent. It may readily be seen that this kind of “trial” was used in instances where the allegation was impossible to prove, and women were the likely sufferers.

Trial by Compurgation: Trial by compurgation was an ancient system whereby a disputant would bring forward friends to swear an oath on his behalf that his story was correct.

This primitive method of resolving a dispute relied upon the not unsophisticated proposition, in an Age of Faith, that where a person had sworn an oath on the Bible to tell the truth, she would be risking his soul to damnation if she lied. But it appeared that many people were prepared to take that risk in order to help a friend.

Trial by Torture: Finally, trial by torture has always been popular, though not in the arena of civil cases but more in cases of criminal conduct or especially heresy or treason. As it always results in a confession or death, the conviction rate is a hundred percent.

But as a means for discovering the truth, it has the disadvantage that people will confess anything under torture, and it is inhuman and revolting. (“A person under torture always wants to die.

Torture is worse than death.” Anonymous Honduran torturer)

The shortcomings of these alternative methods of resolving disputes are obvious, and eventually the common law procedures of trial by judge and jury wholly superseded them in English-speaking countries.

Our legal procedures today avoid the appalling risks inherent in trial by battle, ordeal or torture, and even in the days of greatest piety, merely taking an oath could not ensure that the witness would tell the truth. And yet, our present system suffers from the drawbacks so eloquently set forth by Chief Justice Warren Burger, which accounts for the growth in alternative procedures, of which mediation is perhaps the fastest growing.

“Collaborative Law” is a fairly new system, well suited to marital dissolution cases, where the parties and their lawyers make an agreement in advance to work out the terms of the divorce collaboratively rather than competitively, meaning without using the abrasive and costly procedures of litigation.

What if they cannot?

The agreement requires that, if agreement is not attained, then the parties may proceed with litigation but must obtain new attorneys to do so. If the lawyers fail to reach agreement, they are off the case.

If the parties must retain new attorneys, it greatly increases costs.

Both parties and attorneys thus have strong incentive to reach agreement, and more than that, merely making the collaborative agreement in the first place itself reduces the tension and stress that accompanies the break up of a marriage. Especially where children are involved, a workable continuing relationship between the parents is greatly enhanced by a collaborative process, and so often greatly impaired by the traditional adversarial process.

Of all methods of conflict resolution, only negotiation requires that the disputants talk to each other, even if they choose to do so through a mediator.

All other methods of conflict resolution are essentially unilateral and their common liability is that conflicts handled unilaterally are not really resolved at all.

In searching for justice, one often finds her in the company of her retarded little sister whose name is “revenge.”

The Author

Charles B. Parselle is a mediator, arbitrator, and attorney. He graduated from Oxford University’s Honor School of Jurisprudence and is a member of the English bar, then joined the California Bar in 1983.

A prolific author and sought-after mediator, he is the author of the book, “The Complete Mediator.”

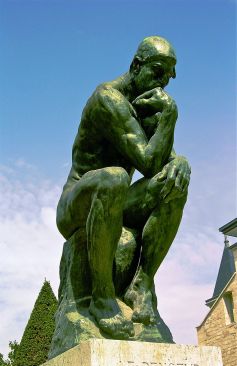

Article picture: janeb13 via Pixabay