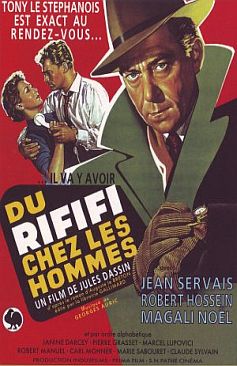

Du Riffifi Chez les Hommes

By Chris Middlehurst

Published on October 12, 2016

The violence in Riffifi is short, brutal and devastating. There are no epic gunfights or gravity-defying bullet dodges: two shots to the head will do the trick. And yet such violence in a film of the ‘50s only dawns upon the viewer gradually and methodically: an early beating takes place, and here Dassin’s use of the tools of his trade reveal a dark genius mind subverting the formulaic tendencies of film noir. Instead of showing a choreographed scuffle, Dassin pans away from the characters and dollies to a picture on the wall, then pans back as the character who’s done the beating leaves the room.

As with the best of filmmakers, Dassin knows that what is more shocking is not what happens on the screen, but what the viewer assumes is happening on the screen, even when it is not.

The audience knows that a brutal beating has taken place, and yet does not need to see it: a similar moment occurs in Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, where the camera tactfully avoids the gruesome event that takes place between the tied-up cop and the cop-hating robber.

One suspects that the QT of today would probably have filmed that scene altogether differently, with buckets of gore, prosthetics and a microscopic zoom where a single camera and a little restraint would have sufficed. In Riffifi, the restraint and brevity of the violence only highlight its terrible and everlasting impact on the victims. There is no lingering or fetishizing of the act: a man pulls a trigger and another dies. The end.

This is in many ways a very modern film, certainly years ahead of the contemporaries of its genre: whilst Humphrey Bogart and Robert Mitchum punched and kicked in ballets of ever-increasing ridiculousness, the heroes of Riffifi were being knocked down like flies with the efficiency of a single, well-aimed bullet. Or worse. But the film challenges so many other film noir genre conventions: the hero is not a loveable rogue but a vicious woman beater with a ruthless code of honour; the hired muscle is not dumb or impatient, but a thoughtful accomplice and a loving husband and father; and the rat is not (as in so many other countless crime capers of that era) a woman with a grudge to bear, but one of the blokes on the job. And there is a stylish nightclub song-and-dance routine that seems to have inspired every James Bond title sequence to date.

Like the best crime caper films of any period, it is the method and preparation of staging the caper that is the most interesting. Dassin condenses the violence in Riffifi to short brutal outbursts, but the scenes in which his gang carefully plan the heist are undoubtedly the longest, the most methodical, and the best. As they meticulously record who turns up when and where on each street corner, figure out how to drill through a hole in the building above without waking the tenants and by chance find an ingenious way to silence an over-sensitive burglar alarm using household items, it gradually dawns upon the viewer how much we want them to succeed, and how much we know, based on countless other movies, that they are bound to fail. In the end, it is not the gendarmerie who foil the robbers, but a rival gang with a plan to split the spoils that inevitably goes horribly wrong. The film’s descent into a bloodbath is not so much a surprise but a sobering reminder of how the characters have placed themselves in far too many perilous situations and that, in film noir at least, the devil always comes to collect his due.

This is not to say that Riffifi is merely a dark, misery guts thriller of a film: there are many lighter moments involving the hired muscleman’s adorable son (ironically pow-powing plastic guns in his cowboy costume) and the urban Parisian vernacular of these characters is tough, hard-boiled and witty. There is even a sense of multiculturalism that reminds one that there weren’t just cabarets and nightclubs in Vienna: the Italian safecrackers, the trip to London and the Spanish go-go girls evoke a world brimming with life and variety. And a Gallic eccentricity invades many of the film’s best scenes, particularly in the build-up to the robbery: the Americans used guns and the English used Mini Coopers. Who else but the French would have the idea to use mayonnaise? Mayonnaise!

The Author

Chris Middlehurst is The New Jurist film review editor. Chris graduated from Leeds University with a BA in English Literature, where he served as President of the LUU Film Making Society and also took elective modules in Chinese, Italian and World Cinema. He currently lives in Leeds and volunteers regulary at the wonderful Hyde Park Picture House, where he urges film lovers to visit if they get the chance!

Article picture: DVD cover of the film La Collectionneuse. Source: Wikipedia.