Op-Ed

By Andrew Wallis

Published on April 28, 2014

Westminster Magistrates Court is a world away from Rwanda or the horrors of its genocide which began 20 years ago this week. But it is in this incongruous setting that the international search for justice against those responsible for the massacre of one million people in 100 days now moves.

Five men – who include a doctor and three former mayors –are fighting extradition to Rwanda where they would face charges of organising and taking part in the unimaginable mass slaughter of men, women and children. The result of the case, scheduled to last until June, will have a major impact not just on the hopes of genocide survivors but also on the responsibility of the UK to meet its international pledge that those accused of the most terrible crimes will not escape justice.

If the five men fail in their bid to have their extradition blocked, it opens the way for dozens of others who fled to the UK to be returned to Rwanda to face trial. If they succeed, the responsibility will switch to the UK to find ways to try those accused in our courts.

What we do know from the UK and other European countries is that the case will follow a familiar pattern of politics being put before justice. Indeed, four of the five men have already escaped extradition in 2008 by arguing that they would not face a fair trial back in Rwanda.

The defence strategy will again be to put the Rwandan Government in the dock. Rwandan political dissidents now in exile, francophone academics and former French military officers are called as expert witnesses. They invariably admit they don’t know the accused or whether they are innocent or guilty. Instead, they take the stand to decry the current Rwandan government and the President, Paul Kagame. The genocide and alleged crimes of the defendant take a secondary place. It is a well-worked formula seen in genocide trials during the past two decades, from Arusha to Paris, and Oslo to Quebec.

But they may find it more difficult to convince the UK court this time. Since 2008, the Rwanda justice system, helped by funding and expert advice from Europe, has been totally remodelled. It has proved such a success that the UN, Canada, Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands have all recently agreed to return suspects for trial. The European Court of Human Rights, with its implacable standards, has also judged the system to be free and fair.

It is not possible, of course, to second guess what the ruling maybe this time. But a decision to oppose extradition should not be the end of the matter. The UK ratified the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. This obligates the UK to ensure those accused of genocide stand trial, if necessary, in its national courts, no matter how costly and time-consuming this proves. This is the route being taken in France and Germany.

It is why the case this week puts into the spotlight the challenge for the UK and Western justice systems of what to do when all those accused of mass murder abroad flee to its shores and claim political asylum or just ‘disappear’ into diaspora communities. Recent horrors in Libya, Ivory Coast, Mali, Sudan, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Syria, for example, have seen an increase in those fleeing to the UK and other European countries in search of a safe haven and a comfortable retirement. Not all are likely to be innocent refugees.

The countries from which they escape are, unlike modern Rwanda, often failed states, still in conflict and with a justice system in tatters. In these cases, extradition is always liable to be denied. But trying them in domestic courts also poses great difficulties.

We have seen in extradition cases in the UK and the Rwanda genocide trials in Paris and Frankfurt, how difficult it is to judge crimes committed thousands of miles away in conflicts, cultures and histories that are little understood. Solicitors struggle to pronounce Rwandan names, locate places or make sense of distances. Witnesses, either in person or by video link, are barely understood because of their basic English or heavy accents.

Both prosecution and defence teams have had to visit central Africa at great expense to do their own investigations. But it quickly becomes clear that their crash courses in Rwandan history, culture, language and the genocide are a little past the elementary level.

Nor has the experience so far of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda done much to support those calling for responsibility to be handed over to an international body. Despite $3 billion dollars and 19 years, the record of the ICTR in Tanzania is mired in controversy including delays, corruption scandals and the failure to protect witnesses, some of whom have been murdered after their identities were revealed.

If the delays so far have been difficult for survivors of the genocide to understand so is the sight of high-profile human rights organisations campaigning on behalf of those accused of these terrible crimes. Justice is pushed aside in favour of the chance to politically attack the Rwandan government. The survivors, yet again, are forgotten.

We cannot allow this injustice to continue. The unhealed wounds from the 1994 genocide will only begin to close when the West becomes serious about justice. The events at Westminster Magistrates Court are likely to be replayed many times in the next few years and the UK must play a full part in bringing timely justice, whether through extradition or internal trials, in such horrific cases that see humanity itself on trial.

The Author

Dr Andrew Wallis is a researcher on the Great Lakes and author of ‘Silent Accomplice: The Untold Story of the Role of France in the Rwandan Genocide, i.b.Tauris, 2014

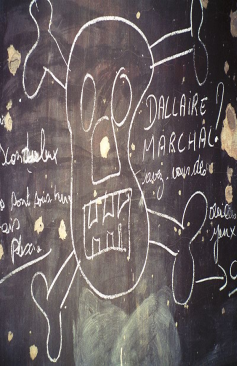

Article picture: Photo No. 2 Kigali school chalkboard. Source: Wikimedia Commons.